The mention of William Jennings Bryan is more likely to arouse groans than applause these days, thanks to the innovative historical-fiction play and film versions of Inherit the Wind, which caricature Bryan as an obtuse, reactionary dullard and present his opponent, Clarence Darrow, as an amiable genius. Also, elements of the actual Scopes Trial were skewed to stack the deck against Bryan’s performance and general intellect (such as Darrow’s actual evocation of a goofy 4,004 B.C. creation date, something Bryan never honored with speculation – beyond the fiction).

Unfortunately, the revisionism of Inherit the Wind and poor educational reportage, for the most part, have obscured or nearly erased Bryan’s urgent support of women’s suffrage, his championing of populist and progressive causes, his essential opposition to war and his wariness of mammoth business trusts. Also, H.L. Mencken’s brilliant incisions, such as the following, didn’t help: “…Neanderthal man is organizing in these forlorn backwaters of the land, led by a fanatic, rid of sense and devoid of conscience.” Actually, Bryan, in a non-senseless, conscientious manner, seemed to thrust from more of a Christ-centered wariness of science lacking a moral sense than a fundamentalist distrust and rejection of science itself.

Nonetheless, like Captain Edward Smith and the sunken Titanic, Bryan seems fated to go down with his ill-fated ship: The State of Tennessee v. John Thomas Scopes, weighted down by his vilification of evolutionary theory. Personally, I think the prosecution and verdict of the trial amounted to a farcical waste of time, but it’s a shame what blunders can ruin a person’s historical reputation.

As for Darrow, I’d bet that a good number of his fans would rather overlook – or, more probably, don’t know about – the less celebrated and under-taught dream cage match that happened about six years later: Clarence Darrow versus G.K. Chesterton. The inimitable Chesterton was much abler in debate than Bryan, and his unflagging sense of comedy dwarfed that of Darrow’s so much that, this time, Darrow seemed the humorless boor. As a contemporary reporter put it, “Darrow in comparison, seemed heavy, uninspired, slow of mind, while G.K.C. was joyous, sparkling and witty…The affair was like a race between a lumbering sailing vessel and a modern steamer.” Also, Chesterton avoided the trap that ensnared Bryan years before, not bothering to trifle over exact cosmogonic figures, asserting that he was “quite comfortable in a completely mysterious cosmos.” Humiliation aside, Darrow showed decent sportsmanship with later praise for his adversary: “I was favorably impressed by, warmly attached to, G.K. Chesterton. I enjoyed my debates with him, and found him a man of culture and fine sensibilities.”

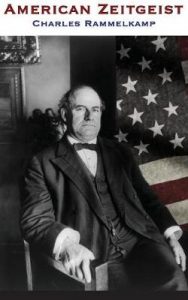

Charles Rammelkamp, whose latest poetry book, American Zeitgeist (Apprentice House Press, 2017), explores the life and careers of William Jennings Bryan, and, to Rammelkamp’s credit, offers a fairer portrayal of the man. I appreciate when writers choose relatively unlikely, unpopular or unexpected subjects as much as I applaud filmmakers who dare to cast actors outside of type – or even non-actors – and achieve worthier cinema as a result. Rammelkamp is an able “director” in this case, having successfully practiced his biographical poetry in The Mata Hari: Eye of the Day.

American Zeitgeist is presented as a series of alternating first-person vignettes, similar to those in Edgar Lee Masters’ Spoon River Anthology, skillfully blending historical fact with poetic fiction and steadily unraveling the diverse, energetic strivings of William Jennings Bryan through the voices of five narrators: Jefferson Powers, William Jennings Bryan himself, Mary Baird Bryan (WJB’s wife), Charlotte Biggs (Jefferson’s ex-wife) and an unnamed student in an Illinois College history course taught by a Professor Lynn.

For me, the book’s star isn’t Bryan but the imaginary Jefferson Powers, who grew up in Bryan’s hometown of Salem, Illinois, and whose career as a journalist for Salem’s The Sentinel goes on steadily during the sociopolitical exploits of wunderkind “Willy.” Jefferson lives his entire life in a shadow of resentment and envy of Bryan.

Insulted as a child when Willy’s moralistic father, Silas, found Jefferson’s father drunk on the ground and sanctimoniously uttered the epithet “drunk,” the permanent underdog holds and nurses intense spite for the Bryans’ legacy, directing the sting of the childhood affront toward Silas’ charmed son. The single incident brands Jefferson like the mark of Cain:

In that instant Willy and I

caught each other’s eye,

and then both were gone,

only a tang of self-righteousness in the air.

“Bryan became the White Whale to my Captain Ahab,” Jefferson comes to realize, and Willy’s secret nemesis derives a kind of fuel from the contrast between privilege and mediocre determinism, as told in “Jefferson Powers’ Jealousy”:

Willy’s success goaded me on

like spurs in a horse’s flanks –

a self-inflicted bite of ambition,

to somehow out-do him:

I was doomed from the start.

Zeitgeist’s drama is not so much the triumphs and trials of William Jennings Bryan, but mostly the familiar scenario of one peer escaping a small town, destined to “make it big,” while the other peer remains there, either languishing or establishing a relatively meager, anonymous living. Jefferson writes for the Sentinel back home in Salem, hearing of and having to report on Willy’s successes. So, Bryan is always fresh, even omnipresent, in Jefferson’s mind, while Jefferson is not a memory – let alone a thought – for Bryan. The unforgivable original sin of Silas Bryan’s insult of Jefferson’s alcoholic father, which has become conflated as young Willy’s sin, replays within every wind of Bryan’s latest accomplishment, as told in “The Voice that Launched a Thousand Nightmares”:

His was the voice that spoke

in my loneliest midnight dreams,

taunting me, challenging me, scorning me.

“A drunk,” I’d hear him mock,

drowning me in my troubled sleep.

After alcoholism finally kills his father, Jefferson desired “nothing more/than to punch Willy’s smug face.” Hence, the impetus to succeed in something, which, for Jefferson, is writing. The main irony of the one-sided rivalry (besides the rivalry’s one-sidedness itself, of course) is the probability that the “smug face” Jefferson remembers was hallucination, a figment solidified over many years. In actuality, Jefferson looks down on Bryan as he looks up at him. While a sense of inferiority is a negative state, it almost always comes with a smugness. The bruised party treasures her/his pain as irrefutable proof of the real or perceived offender’s fault. Also, the one who feels stupid tends to paint the smarter one as even stupider. All of this is often knotted up with a perverse admiration for the offender.

As I became familiar with Jefferson, I thought of him less as Moby-Dick’s relentless Ahab and more Antonio Salieri to Bryan’s Mozart, a la Peter Shaffer’s Amadeus (a product of demonizing artistic license comparable to the fabricated dichotomy in Inherit the Wind). The White Whale may be found in Ahab’s myopic rage and madness for revenge, but as American Zeitgeist progresses, Jefferson’s considerable admiration for his rival becomes more and more evident.

Much later in the book, in a poem called “War,” which involves Woodrow Wilson’s flip-flop into war and Bryan’s offer to serve in the Army (quite a choice for a hardcore pacifist), Jefferson, though envious, shows his paradoxical defensiveness of Bryan when a spiteful colleague named Burt Metcalf bashes Bryan for hypocrisy. “I didn’t see you volunteering,” Jefferson rebuts. “Or myself for that matter.” He goes so far as to confirm Bryan’s sincerity (in spite of his own accusations of “hypocrite”): “You’re right, he’s no Teddy Roosevelt, but he’s a genuine man of peace, Burt.”

The heat of envy lessens by the time Bryan wins the Democrats’ nomination for the House in 1890. “Now I knew he’d bettered me,” Jefferson admits. “In a way it came as a relief,/conceding defeat to my private rival.” Floating with the current rather than swimming against it gratifies, even if one knows she/he is hopelessly lost at sea.

The most pitiful manifestation of this seemingly deterministic Bryan/Jefferson imbalance (or, weirdly, balance – think Road Runner/Wile E. Coyote) lies in their respective romances. Not exactly a Don Juan or anything close to a looker, Willy ultimately marries the comely Mary Baird via attrition, as narrated by Bryan himself in “WJB and the Jail for Angels”:

Mary didn’t fall for me, though,

saw me as a boy with a halo

since I didn’t smoke or drink or dance.

But, persistent, I finally wore her down.

There’s a telling reversal in Jefferson’s fortunate meeting of and marriage to a Charlotte Biggs, who apparently didn’t have to be worn down by courtship, but ends up leaving Jefferson for another man years later:

Charlotte became a block of ice

I chopped at and chopped at,

unable to get her to thaw.

This passage comes from a piece called “Jefferson Powers’ Own Prison,” in which it’s revealed that he’s inherited his father’s weakness for alcohol, eventually ruining Charlotte’s trust and willingness to forgive. In contrast, Bryan’s chopping thawed Mary, and she stayed by his side until the day he died, supporting and helping to further his various endeavors for decades.

As if escaping Salem, catching public/political attention and achieving a loving marriage weren’t enough, Bryan decides to try his hand at journalism, a realm that, in Jefferson’s eyes, should be off-limits, a protected territory of a sort. Now working for the Omaha World-Herald, Bryan is encountered by Jefferson at the 1896 Republican convention:

He shook my hand as a colleague,

but his eyes roamed the city

for more important men,

feigning an interest when I reminded him

of our days in Salem…

…He left me standing there

brandishing my pen and notebook,

a bride abandoned at the altar,

running after the retreating delegates

as if wooing other lovers.

And guess who ran for the Democrat nomination, as the “youngest presidential candidate ever?” Bryan’s failure in the election gives Jefferson “a vindictive satisfaction,” unsurprisingly, though he did vote for him, allegedly due to disdain for “tub of lard McKinley.” In “Nomination” Jefferson relishes Bryan’s false hope:

I’d like to freeze that moment

when Willy accepted the nomination,

capture that time and put it

behind glass, preserved in amber,

that moment of his greatest triumph,

that lofty peak to which he had risen

and would never,

ever,

see again.

If that were possible, the display would have to be placed next to an earlier frozen moment: Silas Bryan’s “drunk.”

Rammelkamp provides a substantial illustration of the idealism and activism of William Jennings Bryan, drives that both made the man endearing and odious. Bryan crusaded for temperance (though not prohibitive legislation), crusaded against the American imperialism of the Spanish-American War, crusaded against the trusts and John D. Rockefeller in particular – and crusaded against human conflict itself:

As Secretary of State I can help bring war

to an end, forever. We will resolve all disputes

on an intellectual plane,

not on the plane of the brute…

…The moral progress of the world

is now ours to shape.

I can’t help but think of the pathetic, rather ridiculous and naïve Kellogg-Briand Pact, which outlawed war between the World Wars.

After such an eclectic and essentially positive life, Bryan then squanders his swan song on opposing the theory of evolution. “The Menace of Darwinism” chronicles his anti-evolution college tours and his support for banning evolutionary teaching in schools. “This was our Willy, all right,” says Jefferson, “passionate about whatever/was his latest cause.”

Jefferson also describes the Scopes Trial as “a heavyweight fight between Wee Willy in one corner,/Clarence Darrow in the other,/better than Jess Willard and Jack Dempsey.” The pounding reaches its pinnacle by the time Darrow gets Bryan into the witness stand. Zeitgeist doesn’t get into Darrow’s weird (and unfair) hypothetical about the Earth’s exact origin and age, but it does bring up the famous exchange in regard to the date of Noah’s flood, in which baited Bryan says, “I don’t think about things I don’t think about” and Darrow quips, “Do you think about things you think about?”

Mary Bryan provides pitiable, affecting narration in “Fool’s Gold”:

My poor dear William jumped to the bait,

certain his eloquence could stand up to Darrow’s mocking.

Oh, the lure of defending Christianity from heathens,

glittering like false gold before his dazzled eyes!…

…But he was no match for this circus master.

Bryan died soon after the trial, and his legacy is still tainted to this day, but, as Rammelkamp notes in his foreword, if Bryan hadn’t died then, he “would have staged another Nixonian comeback.” Yes, even after his own Watergate, Waterloo, whatever, Willy still would’ve whipped whiny Jefferson Powers.

Speaking of Jefferson, American Zeitgeist’s finest moment comes in “Charlotte Biggs’ Legacy,” a poem narrated by Jefferson’s ex-wife, now in her 90s. Transitioning smoothly from the Scopes stuff with the mention of her grandson and granddaughter-in-law attending Broadway’s Inherit the Wind, the piece reveals Charlotte’s regret and sorrow for the long-dead man:

I heard from friends he was found

dead at his desk at The Sentinel,

the year the stock market crashed,

almost seventy years old, a lonely old man.

What follows, in the final poem, called “Footnote,” is a lovely aha moment that made me both kick myself for not putting it together earlier in the reading and smile with admiration at the trick.

Though Jefferson Powers is a believable and care-worthy creation of the author and didn’t really know William Jennings Bryan, Rammelkamp’s grandfather did. But, instead of bequeathing a bunch of sour grapes, this fact inspired the composition of a rather sweet vintage that toasts the complexity of great and anonymous men alike.

– David Herrle