Rating: ❤❤❤❤❤

“My dear young friend,” said Mustapha Mond, “civilization has absolutely no need of nobility or heroism.

These things are symptoms of political inefficiency.”

– Brave New World

…I just marvel.

– Hedy Lamarr

Make Minds Marvel

There are too many spiels on how comic books amount to modern-day mythology while exhibiting the visceral storytelling power of sequential art (well, duh!), so I’ll sidestep the temptation here, instead settling for my habitual introductory tidbit about the quintessentially American nature of comic books, a distinction shared with the respective prophet and messiah of music: blues and jazz. Just as genies can’t be squeezed back into bottles, once superpowered comic-book characters were drawn they were here to stay and became indispensable. I don’t think there’s a higher pop-cultural subject, and I believe that comic-book icons have already surpassed the gravitas and historical durability of the deities of ancient myth and legend. I would never desire an Earth without the superhero concept, nor could I ever imagine such an absence. It is forever within us, and it always will be. And, at least for me, superheroes feel as if they’re part of reality, always in our mental periphery, watching from building tops or walking incognito among us.

In From Hell, what I consider to be Alan Moore’s best work, Sir William Gull says in a virtuosic, allusion-dense monologue: “Scorn not the Gods: Despite their non-existence in material terms, they’re no less potent, no less terrible. The one place Gods inarguably exist is in our minds where they are real beyond refute, in all their grandeur and monstrosity.” (This is an idea that Moore later expanded in his Promethea epic.) I say that the same thing goes for our belief in superheroes. From the ultra-idealistic aspirationalism of household-name Superman to the most cynical anti-heroic antihero of post-Silver Age times, what has remained in comics is quintessential American individualism that still tends to thrill us, to eclipse our sunniest imaginations and overshadow our own shadows.

Ironically, my lifelong love of comic books as an uplifting force is owed much to the rather morose premiere story of Spider-Man, which rawly presents a superpowered person laden with superpowerful self-doubt and sorrow. And, of course, the truly unique visual concept by peerless Steve Ditko (my Jack Kirby) deserves equal – if not more – praise. Considering his eclectic, astute career, imagine a world in which no Ditko had ever existed. Now also remove, say, Jim Starlin, since he’s one of countless comics maestros who would probably never have materialized in such a grim vacuum. And, pertinent to this despicably digressive review, I dare say there’d be no Alex Ross (not to be confused with Surrealist painter Alex Gross or fictional detective Alex Cross), given the apparent centrality of Spider-Man in his own origin story.

Ross considered Ditko’s replacement, John Romita Sr., to be “the pinnacle of artistic achievement” and his facial depiction of Spider-Man “to be the greatest costume design in comics history.” (‘Nuff said, right?) Despite my conditioned awe for Ditko’s artistry, I agree that Romita Sr.’s more substantial Spidey is portrayed in much cooler poses and stylized action. Also, my earliest exposure to the woeful wallcrawler was probably the king-size Marvel Treasury Edition of Spectacular Spider-Man, which features an iconic portrait of Spidey by Romita Sr. on the front cover. I copied that image over and over again as a child, and to this day I visualize it instantly at the mention of my favorite superhero.

But, as much as Romita’s run was brilliant, I prefer the stuff from a little later: Len Wein, Ross Andru, Gil Kane, Sal Buscema, as well as the black-costumed Spidey/Black Cat romance and the Hobgoblin mayhem of the 1980s. Above all, the ultimate sweet spot for me is Amazing Spider-Man 88 to 91 and 121 to 122, the tragic so-called “death of the Stacys” arcs, with Gerry Conway and Gil Kane at the forefront. Already forever traumatized by indirect responsibility for his Uncle Ben’s demise, Peter’s cumulative guilt intensifies with the deaths of mentor/potential father-in-law Captain George Stacy and lover Gwen Stacy at the hands of Doctor Octopus and Green Goblin, respectively. Every time I revisit “The Night Gwen Stacy Died” I’m viscerally crushed – and I’ll never be able to unhear that SNAP heard round the comic-book world.

Re-witnessing the mythic battle between Spidey and Gobby in Alex Ross’ and Kurt Busiek’s Marvels back in the mid-1990s brought back the coda of that eternal story and spiked it with an even harder, adult sorrow communicated through the book’s introspective journalist/narrator/observer Phil Sheldon, who also is forever changed by the very sound of Gwen Stacy’s doom: “[Spider-Man] failed her. They all failed her. I swear I could still hear that flat crack, echoing across the water, echoing in my ears.” Needless to say, my favorite aspect of Marvels is Phil’s acquaintance with Gwen and his depression after her death, something so many people, including his wife, don’t fully understand. While Phil feels the cruciality and emotional impact, his wife basically encourages him to buck up: “To her, like the rest of the world, Gwen was just a girl. Too bad she died, but it’s not like she was anyone important.” I’m reminded of what disillusioned Clark Kent says plainly to Diana/Wonder Woman in Kingdom Come: “Earthlings die. You know that.” But Gwen’s plight transcends common mortality. From her inevitable mortality springs the energy of myth. “They were here to save the innocent,” Phil says of the god-like superheroes. “To save people like Gwen.”

In a much less sympathetic tone, writer Gerry Conway said at Emerald City Comicon: “I really defy anybody to come up with anything memorable that Gwen Stacy ever did other than die.” Okay, but…that death! “I think what we ultimately did was humanize her,” says Ross. “[S]he represents the frail humanity caught up in the supernatural, superheroic chaos.” Marvels, which Chip Kidd calls “a classic feat of pop mythmaking,” was my first Alex Ross experience, and it continues to compel me so many years later. Ross and Busiek intended to present “Marvel heroes as marvels, in the literal sense of the word,” “as if the gods of legend had returned to Earth” (to quote Phil Sheldon again), and this dramatic dynamic is stated in their first proposal to the company:

Stepping away from this strong identification with the characters, showing the readers Marvel heroes from the outside – as if the reader was a normal human being in the Marvel Universe, viewing the heroes the way a normal human would if they were real – with awe, with wonder and with a touch of fear.

They delivered what they promised. There’s nothing like seeing Giant-Man striding above buildings, harbinger Silver Surfer flying through the city before Galactus appears and looms in all his grand menace, and the Fantastic Four, an awesome quartet of balletic coordination, flexing their valiance against him. Surely superheroes in real life would be, to use Alan Moore’s Sir Gull’s words, all “grandeur and monstrosity.” Marvels is rare in that it omits all hero interiority and anything deeper than the physical/archetypal struggle against criminality, which is, in a sense, a stark departure from the Marvel mythos.

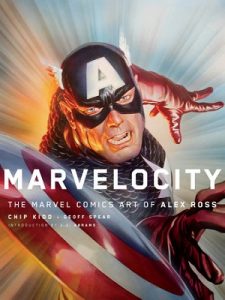

Marvelocity: The Marvel Comics Art of Alex Ross, a collection modeled after Mythology: The DC Comics Art of Alex Ross and, to a lesser degree, The Dynamite Art of Alex Ross, features an opening statement by Chip Kidd (who also wrote the DC book) called “Marvel Changed Things,” in which he explains the general peculiarity of Marvel characters from the beginning, mainly their relatability and their psychological dimension. He points out that since “they had doubts (about themselves and their colleagues), they had worries, they bickered, they struggled with real problems,” Marvel superheroes weren’t relegated to far-removed, semi-divine status. Yes, it seems undeniable and, really, obvious that there’s always a prickliness about the Marvel Universe, less of a typology than DC’s tradition. Its growing pantheon was made of power and bravery, of hearts and minds, but also of flesh and blood – and Alex Ross has leveraged his fundamental artistic realism to emphasize and celebrate this. Likewise, his depictions of familiar crimefighters are simultaneously very human and majestic.

“Beyond Mere Lines on Paper”

In Marvelocity’s introduction filmmaker J.J. Abrams says that Alex Ross works “in a style that owes as much to Norman Rockwell as it does to Jack Kirby” and that “he brings our favorite characters to actual, familiar, relatable life.” There’s a lot to this statement. While it should be apparent that Ross emulates the visual kineticism and exuberance of Kirby, who he claims is his “ultimate artistic hero” and most important influence, the no-brainer Rockwell comparison goes much farther than one might think.

Whether it’s called iconic realism, hyperrealism or photographic realism, in 2015 Ross told Creative Bloq that the realistic method struck him as “the highest point of achievement,” and in Marvelocity he says that the intended end is to present the subject as “a living, breathing thing.” “[H]is realistic renderings of popular super heroes seem to validate these figures for their audience in the same way a motion picture does,” Les Daniels observes in DC Comics: A Celebration of the World’s Favorite Comic Book Heroes, “giving them weight and form beyond mere lines on paper.” I diverge from the motion-picture notion, since I believe all superhero movie adaptations are basically annoying failures, since, despite respecting (mistaking) sequential comic art as perfect storyboards for live action, portraying superhero comics on film is ultimately unachievable, with a few exceptions. Keep superheroes on the printed page or in animation, I say.

Wendy Steiner writes in Venus in Exile that “the thoroughgoing realism of Magritte’s painting was contradicted by the surrealism of his subjects,” which conveniently also applies to Ross’ superhero art. Knowing that Ross works from both live models and photographs, my mind goes to something photographer Sara Lorusso said: “Our body is a work of art, made of curves, mountains and colors and I think it must be shown without filters.” In other words, the artfulness of the body makes it remarkable in itself. Alex Ross seems to perform the trick of emphasizing characters’ actual bodiness while glorifying them at the same time. His art is never not beautiful, nor are the characters he depicts. As Alex Kuczynski says in Beauty Junkies: “Yet beauty speaks to such basic, deep longings, that our search for it remains the most insistent force in our lives. It is an expression of the divine, a symbol we hold up against the inevitable humiliations of mortality.” This makes me think of Ross’ art on a variant cover for the first issue of Captain America: Reborn, of which he said, “The screaming is a release, a triumphant rise from the grave.”

I think the essence of Rossean art is sublime expression of nobility, honor, integrity and – get ready – morality via form, costume, color, tone and lighting. “I want to bring back a sense of morality to comics” Ross is quoted as saying in DC Comics. And Les Daniels declares in the same book that “in fact, it can be argued that his art is the bait he uses to lure readers to the morals at the heart of his tales.” The moral-sense matter, implied and expressed by beautiful images, also is addressed in Mythology, in which Ross views superheroes as possessing “a sense of ethics that would never change…They deal succinctly with moral issues” with less complication and confusion than religion. I can’t help but think of savior-rival Magog castigating Superman for his apparent archaism in Kingdom Come by Mark Waid and Ross: “World’s oldest boy scout…but you wouldn’t change. You wouldn’t get in step, you wouldn’t flex with the times.”

“Glorious. Not…Sordid.”

“Heroes don’t have toothaches, don’t act like the folks next door,” Ayn Rand wrote in a letter to film producer Henry Blanke. Quite hostile to such a notion, Alan Moore, in his introduction to Frank Miller’s Batman: The Dark Knight Returns, rolls his eyes at every traditional superhero “whose every trivial and incidental detail is graven in stone on the hearts and minds of the comic fans,” but he hadn’t yet gotten a load of Alex Ross’ trademark ability to reverently perpetuate those stone-graven details for the sake of true-believing fans while also renewing them. “I’ve always thought there’s a beautiful eloquence of having a connection to something that was designed 50, 60, 75 years ago, that is essentially undiluted,” Ross told Creative Bloq. He also summed up his sort of archaism this way: “What I do, there’s no tongue in cheek. There’s no cynicism.”

Imagine my surprise when I read that Ross gives Alan Moore credit for being “probably the biggest comic influence I’ve had in my life, artist or writer.” (Tied with Jack Kirby, I guess.) Moore, who should be lionized for his Swamp Thing reinvention alone, doesn’t seem to be a warm proponent of nostalgia, though I could argue that his metaphysical incision of genres comes from a basic soft spot for them. Knowing Ross’ Moore fandom makes me understand the uncharacteristic cynicism and disillusionment of the (Don Quixote-like?) Uncle Sam series he and writer Steve Darnall did for Vertigo. A compendium of the United States’ sins since its inception, including lynchings, persecuted Native Americans and (yawn) cruel capitalism, Uncle Sam ended up being, as Ross puts it, “the one thing I’d done that attracted the notice of…Alan Moore.” Zero surprise there. Moore called Uncle Sam “a luminous and moving study of America’s iconographic landscape.” Though I’m not a fan of the series, I view it as an example of a quintessential American art form looking back at and criticizing its cultural progenitor. It contains a sober message that Ross felt he needed to be part of, which is fine. After all, even cheery Norman Rockwell composed The Problem We All Live With, the soul-impaling portrait of poor little Ruby Bridges being scorned on her way to school in “melting pot” America.

a shelf of favorite and pertinent books

If I seem detached from The Cause (whatever that might be at the moment), it’s probably because I’m more Augustinian than Pelagian. My contrarian motto is this: When a cause trumpets, I long for silence; when the frivolous reigns, I crave manifestos. However, there are times for commentary while raking through the human heart’s muck and plumbing society’s toxic depths. I can be as serious and suspicious as any cynic and as miserable as the next shoegazer, but, with all due respect to beloved Moore and others, I’m weary of superhero deconstructionism, and I tend to believe with Sheldon that “the Marvels were supposed to be pure. Glorious. Not…sordid.”

The overdone tearing down of those costumed ideals by the “woke” or by pervasive nihilism sometimes causes me to ask as Phil did to a sidewalk-pacing doomsayer: “Isn’t there enough in this world to frighten little girls? You don’t have to go making them scared of heroes on top of it all!” The addition of more nuance, skepticism, cynicism, psychology and metaphysics in comics is a good thing, without a doubt. The fight-this-weirdo-then-fight-that-weirdo pattern of the early Stan Lee books quickly becomes monotonous, but I think that the complicators have often gone too far, and, to use Sheldon’s words again, “instead of ticker-tape parades, we got doubts – accusations – innuendo.”

Though I adore stuff like Gerard Jones’ Green Lantern: Mosaic, the social commentary in the short-lived Milestone titles and Max Allan Collins’ Ms. Tree, I easily tire of ideological controversy. Fantasy over party, the impossible over politics, myth over moment for me, please. Uncle Ben’s death in Amazing Fantasy 15 should outlast the rather silly Obama cameo in Amazing Spider-Man 583, for example. Over Mark Millar’s Civil War or Brian K. Vaughan’s Ex Machina give me the magnificent Ross-inspired Earth X trilogy, Jim Starlin’s kaleidoscopic Infinity saga, John Rozum’s insane Xombi, Brian Bendis’ Secret Invasion, D.G. Chichester’s Daredevil: Fall from Grace, Brian Holguin’s Aria, and Doug Moench’s and J.M. DeMatteis’ The Spectre.

Mind you, I appreciate a lot of progressive writers, such as comic-book Titans Gerard Jones, Gail Simone (who really made Wonder Woman even more wonderful), Warren Ellis and even Grant Morrison, but for every 100 Denny O’Neils and Mark Millars we need at least one Frank Miller.

The Miller/Ross Polarity?

An artist/writer of libertarian individualism, irreverence, pessimism, iconoclasm, absurdity, ambiguity, anarchy, heart and brutality, auteur-natured Frank Miller is Frank Miller, and everyone else can go fuck themselves. Though he’s a revered comic-book veteran who revived Daredevil, created Elektra and reinvented Batman, he’s also scorned (erroneously, obtusely and often stupidly) for a perceived underlying conservatism and for what many consider to be an increasing aesthetic bizarreness. For instance, his Dark Knight Strikes Again was rejected by even many of his fans as a florid farce rather than what I think it is: a tour de force. Not to mention his pulling a Steve Ditko by espousing Ayn Rand’s adoration of individual excellence, rising above the collective and confident morality, though his greys are sometimes as stark as his blacks and whites – and he’s never dreamed up a character as boring as John Galt.

Undoubtedly confident in his own artistic sensibility, Miller exults in a style that is surrealistic, expressionistic, noir, manga-like, sometimes kitschy, sometimes medieval and sometimes primitive, visionary and shamanic, evoking Egon Schiele, Picasso, Aubrey Beardsley, Marc Chagall – and even some Tamara de Lempicka. Especially enhanced for better or worse by Lynn Varley’s (mostly computer-derived) coloring, it has a psychedelic (Joel Schumacher?) glow, and even its formatting is taken to audacious extremes. For example, there’s a 30-frame page in the DK2! Alex Ross would never! His images barely withstand the limits of a page’s four corners.

Surely, if she’d lived long enough to see it, Rand would’ve appreciated the visual work of Alex Ross, if not for just the Atlantean poise of his subjects and his non-ironic presentation of masculine/feminine bodies. His cover for Captain America: Reborn‘s first issue, presenting Cap as “the American Flag personified,” as he describes it, would have sent her into ecstatic throes, for sure. In a letter to a fan in 1945 Rand described her characters as “personifications of spiritual forces,” which rings like Ross’ “sense of morality,” though there’s almost absolutely no reason to think that he’s a proponent of Objectivism whatsoever, as far as I know. (Though he and Rand do share the same initials. Hmmm…)

One could say that, at least aesthetically, Frank Miller is a polar opposite of Alex Ross, whose art tends toward the two-page spread and exceeding boundaries rather than contorting and squeezing to accommodate it. Frank Miller is the effing Ramones to Ross’ John Williams; Miller’s The Wild Bunch, and Ross is James Bond. Think of this dichotomy while reading what Jenette Kahn, former DC President, says in the introduction to Les Daniels’ DC Comics:

It is fascinating to note that the evolution of comic book art in sixty years has mimicked the development of western painting over the past six hundred years. Fresco painters Giotto and Masaccio, followed by the early Renaissance painters, were concerned with articulating the weight and mass of their figures; they wanted to paint people who could actually exist in space.

Okay. That pretty much sums up Alex Ross, doesn’t it? Now see if the rest of Kahn’s statement evokes Frank Miller:

As the Renaissance reached its apex, mastery of perspective became an all-consuming passion, which reached perfection in Michelangelo’s combination of verisimilitude and dynamism. Once these goals had been achieved, succeeding artists took figural painting in new directions. Some purposefully distorted the body for emotional effect; others flattened or skewed perspective in order to emphasize elements of composition and design.

Just as in Mythology, key points about Ross’ technique are revealed in Marvelocity, mostly in a section called “The Process.” Preferring gouache and rarely using oils, he mainly works from live models and/or photographs, as well as from props and toys. I know that two other creators of realist but fantastic art, Boris Vallejo and Julie Bell, rely on live models and photos, the latter being particularly helpful, according to Julie because “what you’re looking at is already flattened out, which makes it easier to translate into painting.” “You are creating a 2D image with the illusion of depth,” Boris says of painting in general, “so you have to learn to look on objects as a combination of light, shadow and form.” And that’s what Ross excels at. Yes, Frank Miller has mastered “light, shadow and form” in his own way, but his flat-baroque (LOL!) vibe, and his abstractions, contortions and transmogrifications, radically contrast Ross’ supple, proportional figures.

These days, when too many comics are computer-doctored, cartoony and juvenilized – and even the lettering is deathly boring, Ross’ images stand out like rare but relevant antiques. “Absolutely not,” he replied when asked if he resorts to computer enhancement. “For me, it has to be an act of engagement with your hands. I believe the stuff that works well is the stuff that has more life in it, as much of the human hand visible in it.” One of Marvelocity’s treats is the explanation of how the Human Torch’s appearance in Marvels was conceptualized and put together – from photo negatives! Noticing that process details such as sketching and making corrections on a lightbox before the paint is mentioned in Mythology and not in this book, among other things that appear in one and not the other, I’ve concluded that the two books are indispensable siblings.

Deeply influenced by illustrator Andrew Loomis and, as noted ad nauseam, Norman Rockwell, Ross’ art may be realistic, but it also is idealistic. His characters’ materiality may be obvious; they may look like they can sweat from pores. At the same time, they’re Disney-pretty/handsome, attractive faces and forms. His Carol Danvers/Captain Marvel would make, say, Alberto Vargas or Frank Cho wither; even his Vision could woo a real-life witch. We could only be so lucky as to age like his Clark Kent or Bruce Wayne! If he’d been born several decades earlier, Ross could’ve ruled the roost of pulp-magazine cover art. The reason I don’t mind the threadbare Rockwell comparison is the fact that Rockwell himself said that his art depicted “life as I would like it to be,” which also seems to be Ross’ wish. He’s even admitted that he thinks his finished images fall short of his original visual intentions. But, my Lord, how they’ve risen from the really early days, in his Crayon Period.

It Doesn’t Begin Until the Bat-Lady Sings

I’m picky and name-droppy about visual artists in general. On less humble days I call myself a connoisseur or an aesthete; today I’ll relegate myself to buff status. My lengthy list of comic-book artist faves include the likes of Steve Ditko, Jim Starlin, Carmine Infantino, Eduardo Barreto, Paul Gulacy, Mike Grell, Ramona Fradon, Terry Beatty, Colleen Doran, Joelle Jones, Jim Steranko, Paolo Serpieri, Alfredo Alcala, John Romita Sr., Mike Kaluta, Brian Bolland, J.H. Williams III, Stephen Bissette, Bill Sienkiewicz, Amy Reeder, Ming Doyle, June Brigman, Howard Chaykin, Denys Cowan, Gene Colan, Sal Buschema, Jacen Burrows, Marie Severin, Melinda Gebbie, Dave Sim, Adi Granov, Frank Cho, Mike Mayhew and Adam Hughes (to name one or two). And, of course, Alex Ross is among my favorites, though I feel that he belongs on a one-man list, for both his aesthetic profundity and gobsmacking prolificacy. Plus, Rossean art is “too big” for the eyes sometimes and can only be absorbed incrementally. When every frame is a stand-alone work of art in itself, one risks exhaustion – but not necessarily in a bad way. His work should endure for centuries and glow in the pantheon that includes folks such as Bouguereau, John Singer Sargent and Artemisia Gentileschi. (No joke!)

Born in 1970, Nelson Alexander Ross retreated to the comic-book world to deal with the childhood isolation he experienced after his family moved to Texas from Portland, Oregon. His destiny descended on him via his talented mother, Lynette, who had gone to Chicago’s American Academy of Art and once worked as a professional fashion illustrator. The DC Ross book shows a drawing she did of a Bat-Lady in a notebook in 1941, and Marvelocity features her sublime renditions of Captain America, Hulk, The Vision and Thor from 1978. Ross also ended up going to the same Academy and gradually refined his skills into the expertise we now take for granted. He went from rudiment to re-creating the legendary covers of his idol Jack Kirby. Surely Lynette destined her son for the palette.

Perhaps the primary treat of this book is the presentation of selections from Ross’ childhood illustrations and figural crafts, whose poignancy are all sharper when compared to his later art. For instance, we get to see the compressed astronomic leap from five-year-old Ross’ pencil-and-crayon “Spidey” nabbing bad guys to a radiant, lifelike print of a webcasting Spider-Man done in 2010. Many more comparisons follow (some side-by-side, some not): Hulk at age 7/cover of Hulk 5 in 2014, homemade superhero stamps at age 8/Gwen Stacy and Spider-Man on an Upper Deck trading card in 2005, sloppily penciled covers for “The Ivendors” and Invaders at age 7/cover for Invaders Now! in 2011, an Uncanny X-Men illustration (evincing much maturation and honed talent) at age 14/the epic cover for Uncanny X-Men 500 in 2008, and homemade X-Men, Sub-Mariner, Fantastic Four and Iron Man figures at age 11. Made from materials including cardboard, colored paper, Silly Putty and fabric, those figures were creative prototypes of Ross’ future formal style, as well as the lifelike busts he designed with sculptors Larry Malott and Mike Hill: Silver Surfer, Green Goblin, Hulk, Spider-Man, Nightcrawler – and DC characters too. The realism of the heads is…unreal.

After doing ad-agency storyboarding Ross landed gigs for Terminator: The Burning Earth, Kurt Busiek’s Astro City: The Tarnished Angel, Miracleman, et al. And finally, in 1993, he took center stage with the inimitable Marvels. By the time Earth X, Universe X and Paradise X came out Ross was an in-demand comics powerhouse, as he is to this day. When his art isn’t filling the pages of a book, it can be found on countless covers, movie posters and special prints. It even appears in the opening credits of Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man 2. This guy even creates his own logos, for FOOM’s sake, ever since he “figured out how to render topography out of pure intuition,” as he puts it.

Aside from an impressive re-creation of an Iron Man versus Sub-Mariner battle in a Jack Kirby-drawn Tales to Astonish issue, Ross and Chip Kidd collaborate in a “Creating a Story” section at the end of the book, as they did in Mythology. In Marvelocity it’s Spidey versus the Sinister Six, after the Steve Ditko-drawn first issue of The Amazing Spider-Man Annual (1964), but with Green Goblin and Lizard substituting for Kraven and Vulture. I won’t spoil it here, but readers should expect an unexpected ending cooked up by Kidd.

Needless to say, Marvelocity is jam-packed with goodies, and with goodies fighting baddies. And the book’s very title is radically apt: Marvel comics effing exude velocity. My mind goes to something Ross told Entertainment Weekly’s Christian Holub: “[W]hat’s always separated the two for me is Marvel’s material has always had a kinetic quality to it…There’s a kinetic energy and a chaotic energy that embodies Marvel’s stuff.”

Saint, Sinner/Super, Human

My aesthetic tastes run the gamut. I can swing from a shadowy, scribbly Eddie Campbell to a lofty Alex Ross without blinking. And my pendulous soul allows me to see beauty in both the sacred and the profane. There’s a time for pin-up perfection and a time for the what-you-see-is-what-you-get familiarity of marital bedrooms in all its bruised, razor-burned, cellulitic glory. There’s turn-on to be found in both pornographic John Currin and Rubens. Sanitized, Photoshopped Playboy-type fantasy tableaux needs the counterweight of hairy as-is Lee Friedlander nudes. Some days I want to lull away in Gibson Girl-sugar-and-spice-nice Gwen Stacy’s timeless eyes, and other days I desire a wham-bam one-minute stand with an amoral, sleazy Sin City dame.

Also, beyond skin-depth, murky villainy can be much more interesting than the Lone Ranger’s glittering badge. After all, as Gilbert says in Oscar Wilde’s The Critic as Artist, “there is more to be learned from the sinner” than from the saint. But sometimes portraying saintly superheroes is far from shameful. Without soaring marvels our vulgarity would drown us. Despite my soul’s pendulousness, my heart fundamentally hungers for ambrosial Rossean visual idealism, which automatically calls nobler notions to the surface.

“Only human” isn’t necessarily only human. Yes, to appropriate Alan Moore’s Sir Gull’s statement on gods again, the irrefutable reality of superheroes, “in all their grandeur and monstrosity,” may be a mental situation, but we mustn’t forget that if such marvels exist in our minds, then we possess marvelous potential – marvelocity! – despite flesh, blood, fallibility, mortality and gravity. But there’s realpolitik to this metaphysic. Where there are superheroes there are supercriminals; good and evil seem, for now, ontologically symbiotic. We must beware of what author Anthony Burgess saw as the inevitable repeated disappointment of liberalism; humanist/humanitarian spite can degenerate into inhumane Robespierrean tantrum. We are certainly not our own heroes in the long run. If humanity’s our only savior, then humanity’s fucked, I always say.

Despite periodic bouts of utopian hope and unanimous cheer, through lulling chimes and laughter I will always hear the grisly SNAP of Gwen Stacy’s neck. The trick is not to be tricked into total despair and rejection of the Romantic (which, essentially, is what Alex Ross expresses in his art). Wiseman G.K. Chesterton wrote in “The Position of Sir Walter Scott” in 1901:

The centre of every man’s existence is a dream. Death, disease, insanity, are merely material accidents, like toothache or a twisted ankle. That these brutal forces always besiege and often capture the citadel does not prove that they are the citadel. The boast of the realist…is that he cuts into the heart of life; but he makes a very shallow incision if he only reaches as deep as habits and calamities and sins. Deeper than all these lies a man’s vision of himself, as swaggering and sentimental as a penny novelette.

Cynics! Social-justice critics, reactionaries! Shoegazers and naysayers! We need a break! Don’t scorn the gods! Fantasizing the feats of flaming, flying, hefting, hurling “dangerous, beautiful and thrilling” superbeings is a lifeline, not a sham. “Look up, why don’t you,” scolds Marvels’ Phil Sheldon. “[L]ook up for once in your lives – !” Perhaps rivalling that Chesterton clip, Stan Lee’s trademark exclamation essentializes the Marvelous spirit: “Excelsior!”

Though Marvelocity is about Alex Ross’ seminal immersion in and fateful contribution to the Marvel Universe, he credits The Electric Company’s “Spidey Super Stories” as his first exposure to the webslinger. I also remember the delight of seeing him in weird, wiry “reality” on TV. Recalling the show in Marvelocity, Ross sums up the nature of his exuberant art when he exclaims, with Frankensteinian yet non-hubristic elation: “[T]here he was, the costume was vibrant, he was alive!”

David Herrle