Rating: ❤❤❤❤

Nowadays, Lord Alfred Douglas’ “love that dare not speak its name” dares to speak its name – and then some. In fact, it needn’t dare at all, because, for the most part, non-heterosexual speech is popular, widespread, bold, prevalent – and, yes, even moralistic. For me, the love hinted at in the poem by Douglas covers gay, lesbian, trans, queer, bisexual and intersex folks. (If I left anyone out, please forgive me.) Perhaps never before have sexuality and gender been such hot topics, and they certainly haven’t been so widely questioned, studied and politicized (for both good and bad). What is heartening is the existence of more receptive forums and inclusive insights in regard to non-traditional sexual orientations and gender types.

While gay and lesbian activism has yielded extremely progressive results in the last few decades, transfolk continue to struggle for respectful recognition. All of them are in an uphill battle, but female-to-male transitions are even less accepted than male-to-female ones – and the latter fare better only if they “pass” with convincingly feminine appearances. So, in a sense, the traditional gender binary is in turn reinforced or validated by individuals striving to achieve the expected appearances as closely as possible. This isn’t to say that the binary is fundamentally problematic or tyrannical. Though it can serve as a negative gauge of who “passes” and doesn’t, it also can be spun as a marker for a sort of solar-spectrum chart on which many different gender gradations and nuances are visible.

This wider spectrum allowed the enigmatic Candy Darling to fluctuate between drag queen and all-American platinum bombshell back in the 1960s and 1970s, and it allows actor Tilda Swinton to thrive as an androgynous icon, as well as the perfect embodiment of Virginia Woolf’s Orlando – not to mention the unlikely transformation of Bruce Jenner into Caitlyn Jenner. Activism, apologetics and acclimation are made possible by celebrity trans figures such as Paris Lees, Gigi Gorgeous, Janet Mock, Hanne Gaby Odiele, Jazz Jennings, Pidgeon Pagonis (creator of The Son I Never Had and What Do People Know About Intersex?), Laverne Cox, Amanda Lepore, Willie Wilkinson, AJ Ripley and Kye Allums from an essentially leftist perspective, and even conservative transfolk are represented by the outspoken Theryn Meyer and provocative Blaire White. (Of course, there are the many “everyday” individuals who find themselves navigating not-so-simple gender waters.)

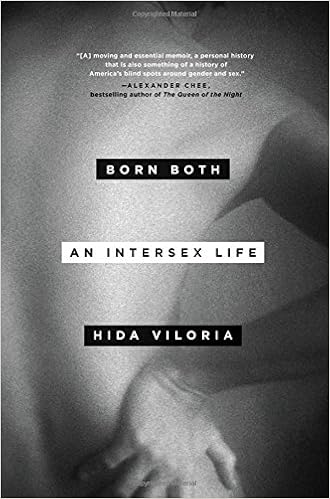

And then there’s the relative flatline of the socio-political clout of the intersex community. “Hermaphrodite” has a more familiar ring than “intersex,” of course, but hermaphroditism still seems to be on a mythical level, not quite taken seriously by the public at large: an oddity or curiosity rather than a flesh-and-blood-and-mind reality. Thankfully, awareness of intersexuality is growing, thanks to people such as Hida Viloria, an intersex lesbian who evolved from gender confusion to gender fluidity and found both he/r (as she pronouns herself) voice and niche as an activist, lecturer, author and consultant for intersex/non-binary gender issues. Aside from serving as chair of the Intersex Campaign for Equality (OII-USA), she has written for the Psychology Today blog, the American Journal of Bioethics, Ms., The Advocate and The New York Times, and she’s the author of a pamphlet entitled Your Beautiful Child: Information for Parents and a new memoir, Born Both: An Intersex Life, which is dedicated to, along with Hida’s mother, “all the intersex people who have had to live, and die, in secret.”

Let me put this out there right away and without finesse: Hida has a huge clitoris. It’s been disproportionately large since childhood, so much so that her parents, Hida’s mother confessed much later in life, thought their newborn daughter was a boy at first. In fact, when Hida becomes sexually aroused, “it gets erect and looks like a tiny dick.” Fixation on her clit size resulted from a doctor’s impolite query after an emergency operation due to a dangerous ectopic pregnancy, which was the bitter consequence of Hida having been raped while drunk at a nightclub. For much of her life Hida mistook this oversized sex organ as a source of confusion and embarrassment, a negative symbol of extreme difference. Eventually, she reevaluated it as a unique gift and, in many cases, a desirable thing which continues to invigorate her sex life. And, since the rest of her physical features had always been ambiguously masculine and feminine, Hida found that she possessed a rare superpower of sorts: the ability to choose and fine-tune her gender characteristics at will, even at a whim: “As long as I remain dressed though, I can pass just as easily for a boy as a girl, depending on the clothes I wear.”

At the Litterbox, a queer club, Hida met and fell for a stunning redhead named Christina. When the two made love, the magic of her “amazingly mysterious organ” was beyond obvious: “a great force begins to unleash itself” and “she screams with me as her body receives it.” During sex another time, Christina playfully said, “You’re such a boy.” Later down the road a gay guy named Jonathan echoed this when he said, “You seem like a boy to me. A cute boy.”

After such a long period of confusion, by the time Hida realized that true nature, she embraced her gender-flux power with gusto:

I’ve been dealing with polarized gender-role requirements for so long that I had no idea how liberating it would feel not to. To be able to look however I want – butch or femme, male or female, both, or something else – all the time.

Her attendance at Burning Man in 2000 was a turning point. Uninhibited and dancing to DJ music, she felt the hypnotic force of her having been “born both”:

I look very Is that a boy or a girl?…My energy moves back and forth from masculine to feminine and everywhere in between. It seems to mesmerize the crowd…I throw some love at both the girls and the boys because I can tell they see me for who I am.

Hida substantiates the pride-worthiness of her bothness by referring to Herculine Barbin and the myth of Hermaphroditus, and she relates a pep talk her friend Jade gave her once: “Every spiritual philosophy talks about how it is to unite the feminine and masculine polarities. Even Jung talks about the hermaphrodite representing the union that’s necessary for psychological transformation.”

In other words, there’s a sort of alchemy in this union of polarities, something that even so-called straight folks can’t resist honestly. Though some males responded to her clitoris with disgust (for whatever silly reason), enhanced desire from others was her main experience. Here’s my favorite passage in the entire book: “The most common reaction I’ve had, though, is a kind of hunger. Sure, there might be an initial moment of surprise, but I’ve discovered that people tend to love surprises in bed. They make them ravenous.”

Hida’s self-acceptance and sexual embracement didn’t happen overnight, however. For quite a while she didn’t even have an adequate way to classify herself. Then, in 1995, she noticed a SF Weekly article called “Both and Neither,” in which she first encountered the term “intersex.” “Is this the word I’ve always lacked?” she wondered. “Is this the word to describe my very private, secret difference?” Still, she struggled with her self-identification as a lesbian, informed, in particular, by The Hunger movie, starring Catherine Denueve and Susan Saradon: “That’s what I’d imagined lesbians looked like: two feminine, pretty women together. But much to my disappointment, in the real world it seems like all the pretty lesbians want women who look and/or act like men: the butches.”

After sexual involvement with some males and finding no satisfying spark with them, Hida knew that she preferred females, but she was attracted to feminine ones. And she felt that courting lipstick lesbians would require her to change herself, squelching her enjoyment of appearing feminine: “…I’ve developed a huge love of makeup…It’s probably in part to make up for feeling so ugly in middle school, but I really do like putting on makeup.” Since she had “absorbed those ideas that feminine women are into masculine men – or masculine women if they’re lesbians,” she “tried to be more masculine, for both reasons.”

Sadly (as far as I’m concerned), Hida bought into the popular rejection of cosmetics and decoration (a topic I’d rather discuss – and reject – in a different forum) and stopped making herself up. “[S]uddenly, beautiful gay men are staring at me with open, unabashed smiles,” she marvels. Her intersex sea legs were strengthening and gaining agility. Then the gender pendulum swung back again when Hida dated a woman named Audrey:

She doesn’t ask me to change my style; I just sort of fall into it given the effect that my looking feminine has on her. I start wearing some of my less boyish outfits and wearing makeup, because I love seeing Audrey’s eyes light up when I do. I’m crazy about her, and I want to turn her on as much as possible. However, I’m also discovering that I don’t want to live out the rest of my days as solely a man or solely a woman.

Intersexuality’s fluidity and resilience are evident in the fact that after a breakup with another woman, Hallie, Hida quit makeup again and made herself look “more androgynous than ever.” In a sense, her outward appearance was a barometer of internal conflict.

After struggling with whether or not to accept an invitation to Tranny Fest, Hida questioned her feminine side and how far she from it she might have been drifting:

I’ve been through too many experiences that are uniquely female – like getting pregnant after being raped – to disconnect completely from that part of myself. Plus, the rebel activist in me has always preferred to side with the underdog anyway. So for now, I’m holding on to my f, even though what I feel inside is different – something I still haven’t found the perfect name for.

Hida’s quest for that “perfect name” intensified after Australia lawfully established “X” to mark a third gender and the International Civil Aviation Organization designated “X” for the same after that. Then she read a bothersome editorial on the Psychology Today blog: “Australia’s Passport to Gender Confusion: Why I’m Not Thrilled with Australia’s Regendered Passport System” by Dr. Alice Dreger. Hida rebutted the article with “X Marks Evolution: The Benefits of ‘Indeterminate Sex’ Passport Designator.”

An apparently adequate alternative pronoun for gender, ze, struck Hida. Ze was first used in Dungeons & Dragons in the 1980s, and then in Nearly Roadkill, a novel by Kate Bornstein. After wishing that all humans would agree on referring to each other as “per for person,” an idea from Marge Piercy’s Woman on the Edge of Time, helped Hida reach this soberer conclusion:

Because my gender identity has the potential to change, choosing a nonbinary pronoun, and asking everyone to say it in reference to me forever, feels like more of a commitment than I want to make – especially because at different times or sometimes all at once, I’ve felt like every pronoun.

Attempting and failing to get through law school to advocate for intersex folks, Hida gradually learned that her talents and energy thrived in other forms, which coalesced into an impressive CV: inclusion in the Hermaphrodites Speak and Gendernauts documentaries, appearances on Inside Edition, The Oprah Winfrey Show and 20/20, non-discrimination activism in response to the Olympics/Caster Semenya’s controversy in 2009, opposition to stigmatization of non-hetero sexualities as mental disorders, and articles published in American Journal of Bioethics, The Advocate and Ms. She also wrote “Open Letter: A Call for the Inclusion of Human Rights for Intersex People” for Stockholm’s Second International Intersex Forum, and caught the attention of Charles Radcliffe, senior LGBT rights advisor for the UN.

Growing up with an abusive if not psychotic father and a mother who, though loving, couldn’t really connect with the intersex thing, Hida had to come to terms with her sexuality on her own. Down and out to the point of homelessness at one point, she kept striving and listening to the uncomfortable but assertive spirit within. Almost as an encore for her recognition and earned dignity, Hida and her mother finally shared an affectionate, validating discussion about Hida’s identity. And, thanks to fate’s usual indifference, her mother died of a brain aneurysm not long after. Devastated, Hida fell into a depressive slump for quite some time, but when she broke out of it, epiphany welcomed her:

I suddenly realize that my connection with my mother had kept her beliefs alive inside of me: her beliefs that I would never be able to find lasting love as a lesbian. She’s dead now though, I think to myself, and those beliefs died with her. She doesn’t have them anymore, wherever she’s evolved to, so I don’t have to have them either.

Perhaps as profound as the previous passage are Hida’s words in reaction to the death of the great Joey Ramone in 2001, words that bind the essence of Born Both in a nutshell:

I admired Joey. He was weird-looking and weird-sounding, but his creativity and spirit were so strong that they burst onto the world stage, forever searing a mark of rebellion onto our cookie-cutter society. He showed everyone that you don’t have to fit into the mainstream mold to shine and soar.

– David Herrle