Rating: ❤❤❤❤❤

Spouses of very famous people are usually seen as representatives or extensions – even appendages – of those very famous people. For the most part, this is especially true for Presidents’ First Ladies. Even though most, if not all, of them have been quite active and instrumental, assisting the President himself and/or attending to various White House matters and important projects, most of them are still regarded in light of their husbands’ personalities and statecraft rather than as independent movers and shakers. Abigail Adams, who was indispensable to John Adams, was nicknamed “Mrs. President” due to her prominent role in both the founding of the United States and the political arena. Sarah Polk had quite an active role in helping to run the presidency. Eleanor Roosevelt needs no accolades, of course. However, each of these women is still relegated to First Lady status, there but for the grace of their husbands’ elections to power.

Though it may seem strange to some folks, I think of Coretta Scott King as one of America’s First Ladies, and it follows that I consider MLK to be on par with the Presidents. (In fact, he’s worth than several of those presidents combined.) MLK comes and goes in cultural awareness, and, thanks to the lovely film Selma (and, sadly, the increasing racial tension in the United States over the past several years), interest in him and his legacy seems to be in resurgence. However, even Selma essentially kept the Coretta Scott King role to the side, unintentionally reinforcing that representative/extension/appendage perception of living/dead legends’ wives.

A couple years ago, I read and treasured Cornel West’s and Christa Buschendorf’s Black Prophetic Power, a book containing dialogues between the two about selected giants of the so-called black prophetic tradition: Frederick Douglass, W.E.B. Du Bois, Ella Baker, Malcolm X, Ida B. Wells and Martin Luther King, Jr. Of course, though there are many more folks who qualify for inclusion in such a book, there must be a limit. For me, two more names should be added to the chosen pantheon: Daisy Bates and Coretta Scott King.

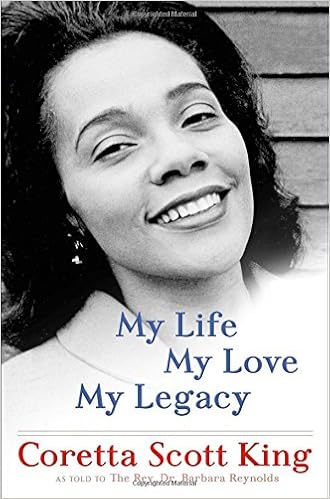

Thankfully, newfound and more informed appreciation for Coretta herself can be sparked by her posthumously published memoir, My Life, My Love, My Legacy, which is co-authored by Reverend Dr. Barbara Reynolds. Though Coretta put out a couple MLK compilations and an autobiography decades ago, those books focused on her husband and were intended to keep his legacy alive. Finally, her legacy is the focus, and perhaps a Selma-level biopic based on this memoir is in order.

With afterwords by Andrew Young, Maya Angelou, John Conyers, Barbara Williams-Skinner, Myrlie Evers-Williams, Patricia Latimore, Bernice A. King and Barbara Reynolds, My Life, My Love, My Legacy allows Coretta to assert herself as herself, to focus on her accomplishments with and without her husband: “There is a Mrs. King. There is also Coretta. How one became detached from the other is a mystery to me.” In spite of his conscientiousness, MLK could be insensitive to Coretta’s agency. Coretta recalls this honestly in the following passage:

Did Martin ever understand how deep my inner calling was? I don’t think so. It transcended even our marriage, and he sometimes struggled to capture its essence. Once, when we were talking about the importance of ensuring that our children received a proper amount of attention from their parents, he blurted out, “You see, I am called, and you are not.”

Coretta makes it clear that her husband wasn’t always this way, and that he usually encouraged her to pursue her calling, but MLK also was a man of his time as much as he was a visionary in some respects, so he did prefer a housewife to an activist. “You know, women are hero-worshippers,” he told Coretta in the early days of their courtship. This fundamental male chauvinism was shown in a larger context by the male leaders of the civil-rights movement who excluded or marginalized women activists and speakers. In fact, none of the prominent and instrumental females in the movement spoke at the event, except for Daisy Bates (in place of absent Myrlie Evers) and Gloria Richardson, who got the word “hello” out before being silenced. And, disgracefully, none of the women attended the signing of the Civil Rights Bill of 1964.

Coretta had quite a life, quite a life of an individual, and quite a life deserving of a legacy. She picked cotton as a child, whites burned down her family’s house when she was fifteen years old, the Jim Crow laws guaranteed injustice, her father, Obadiah, carried a gun to deter would-be assailants and lynchers: her childhood wasn’t the stuff of Norman Rockwell, to say the least. Eventually her father built a new home on private land, and he owned a saw mill that was soon burned down. What did Obadiah do? Give up in despair? No, he built a grocery store/gas station in its place. And, on top of that, he helped those who couldn’t afford goods from the store, putting himself in debt for their sakes. Coretta’s mother, Bernice, was more cautious of whites than her husband. From her Coretta inherited musical talent, and from Obadiah she inherited the grit and benevolence necessary to acclimate to her future husband’s brave drive and even his easier-said-than-done concept of nonviolence in the face of dangerous oppression.

The memoir covers young Coretta’s experiences at Lincoln Normal School, including her acquaintances with Quakers (who influenced her greatly) and her befriending of a boy named Bayard Rustin, who went on to join MLK’s ministry. She went on to Antioch College in Ohio, where she dated a Jewish student and learned a lesson about the risk of interracial love in a racist society. A bigger lesson came when she started the student teaching phase of her education major. Because of her race she was forbidden from doing so at local Yellow Springs and had to commute to Xenia, Ohio. In spite of her admonishments to the college administration, the status quo remained. (It’s no surprise that Antioch’s president’s dog was named Nigger.) Coretta’s awakened sense of injustice and the need for justice inspired her to support Henry Wallace’s presidential run, and she went to see Paul Robeson speak. Eventually she decided to capitalize on her musicality and attended New England Conservatory by 1951. And, of course, a friend set her up with a young man named Martin Luther King, Jr., who was affiliated with Atlanta’s Ebenezer Baptist Church as an ordained minister.

Coretta also inherited and carried on a deep devotion to Christianity. Her sincere faith kept her from blowing over in both the winds of social change and the blasts from hateful and murderous opposition. “To discover what you’re called to do with your life, I believe you have to be connected to God,” she writes in the memoir, “to that divine force in your life, and that you have to continue to pray for direction.” Her prayerful connection included a spiritual fearfulness as well: “I was afraid of committing a sin that would condemn me to burn in hell instead of joining God in that mysterious heaven hidden beyond the clouds.” Far from creating negativity or neurosis, this eschatological sense prepared her to keep up with MLK, who “was constantly examining himself to see if there was any sin that had crept into his life,” “was a much more moral person than most of the people around him” and “never would have stepped away from Christianity.”

Christianity, of course, also factored into her and MLK’s trust in a divine historical plan. Once the civil-rights movement intensified exponentially after Rosa Parks ignited the Montgomery Bus Boycott and things led to the relatively miraculous Brown V. Board of Education, Coretta wondered, “Why then?” “The dam burst,” as she put it, at a particular time and in particular places in history, due to “something Martin used to call the ‘divine dimension’…’There comes a time when time itself is ready for a change,’ he offered…The leaders do not ask for the task, but are tracked down by the spirit of the times until it consumes them…” MLK attributed his motivation to Christ and his resistance technique to Gandhi, and, coincidentally (perhaps inevitably), he met their fate of martyrdom in the end. Right after the assassination of JFK, he said to Coretta, “This is exactly what’s going to happen to me. I keep telling you, this is a sick society.”

Coretta’s and MLK’s remarkable partnership began officially when MLK’s father, Daddy King, married them in 1953. By 1956 MLK’s ministry had grown in both efficacy and popularity, and their house was bombed while Martin was away. Luckily, Coretta, daughter Yolanda and friend Mary fled to back room just in time. The deadly motive of the culprit(s) became evident in what was said in an anonymous phone call shortly after: “I’m sorry we didn’t kill all you bastards.” Instead of resorting to retaliation when he returned to the house, MLK rejected aggression and said to angered friends who wanted violent reprisal, “We must love our white brothers, no matter what they do to us.” His Christly motivation and Gandhian passive resistance certainly won out in such a tense, testing moment. It also helped him to control a natural reaction to attempted murder. A black woman named Izola Curry stabbed him in the chest at a signing of his book, Stride Toward Freedom, and, in a forgiving spirit, he expressed his hope that her mental derangement would be cured and that she’d lead a successful life someday. (Incidentally, before paramedics arrived, MLK refused to have the knife removed, which kept him from dying due to a punctured aorta.)

My Life, My Love, My Legacy covers the highlights of turbulent, dramatic civil-rights activism: the racial tension in Birmingham and the terror of commissioner Bull Connor, the breakout of protests and sit-ins, MLK’s arrests and the kind aid of Harry Belafonte, Robert Kennedy and JFK, the origin of Letter from a Birmingham Jail, the KKK bombing that killed four black girls in Birmingham’s 16th Street Baptist Church, the planning and execution of the action in Selma, Bloody Sunday on the Edmund Pettus Bridge, the horrible voting situation among blacks, the formation of the Poor People’s Campaign, etc. The book also covers the planning for the March on Washington, and I learned that MLK’s world-famous “I have a dream” phrase originated in a speech at Cobo Hall in Detroit a year before the March.

Assailed and impugned from all sides, MLK had to contend with harassment by even J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI, which might have faked a threatening letter advising him to commit suicide rather than get murdered. Rumors and allegations of MLK’s habitual infidelity haunted the Kings, but Coretta denies that her husband was adulterous: “All that exists about my husband is innuendo and hearsay.” MLK was badgered and maligned to the end, and there were two mass feelings after he was assassinated, as he anticipated, in Memphis in 1965: relief for his enemies and racists, and grief over the loss of a hero who’d done so much and could have done so much more. I like to think that he lived just long enough to achieve his calling and to change the dignity of blacks in the U.S. forever. The preponderance of MLK-centered information in this memoir that’s supposed to be primarily about Coretta emphasizes his pervasive presence and sociopolitical activity.

Yes, back during her time with MLK Coretta attended Women Strike for Peace event in Switzerland, helped prepare her husband’s speeches, performed concerts, etc., but her activity really took off following her husband’s death. She helped create the Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial Center (King Center), was instrumental in revitalization in Auburn, Alabama (for which Nixon didn’t help with funds but George Romney came through), co-founded the Black Leadership Forum and worked for justice in South Africa. I was surprised to learn that two of MLK’s friends from back in the day disappointed her in the 1980s. She didn’t support Jesse Jackson’s run for president because she “felt that he needed to stop being so self-centered and to stop using people,” and Ralph Abernathy continued the charge of her husband’s marital infidelity. This helped Coretta choose an independent position in her endeavors. She wrote in a letter to press in 1988 that MLK’s “dream is not partisan…I am not endorsing one party over another.” Her integrity and respectability even won out over the unlikely person of Henry Kissinger, who said to her in an encounter, “Mrs. King, you know something? You all were right and we were wrong about Vietnam.”

My Life, My Love, My Legacy is told in the voice of an American treasure, by an honorary First Lady. Thanks to her full and important life, I think it’s safe to refer to MLK as the husband of Coretta Scott King.

– David Herrle