Rating: ❤❤❤

“A star of the first magnitude, he rose in the night of American slavery, attracted the admiring gaze of the civilized world, and so thrilled the hearts of men that they broke the chains of all his kind in the hope of further enriching the firmament of lofty human endeavor with stars like unto him.” – Ensal, The Hindered Hand (1905)

Light in “the Moral Dungeon”

In the introduction to an edition of the Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, lawyer/judge George L. Ruffin says that “Frederick Douglass stands upon a pedestal stands upon a pedestal…” And Cornel West, in his dialogue with Christa Buschendorf in Black Prophetic Fire, puts “Frederick Douglass at the top” of both Abolitionism itself and President Abraham Lincoln’s grand moral action in regard to establishing an anti-slavery Union in the United States. Yet West also stresses that “there is no great Frederick Douglass without William Lloyd Garrison,” which, for me, emphasizes a fundamental tension, rather than harmony, within the colleagueship of Douglass and Garrison: the two brightest colors on the pro-constitutional/anti-constitutional spectrum.

In contrast to the Garrisonian distrust of the U.S. Constitution, due to tracing the immoral legitimization of slavery to the marrow of the document itself, Douglass realized that it “was in its letter and spirit an anti-slavery instrument, demanding the abolition of slavery as a condition of its own existence as the supreme law of the land,” and he laid out his reasoning in a speech in Scotland in 1860: “The Constitution of the United States: Is It Pro-Slavery or Anti-Slavery?” Douglass stood fast against a good number of Abolitionists who agreed with Garrison, insisting that “the Constitution of our country is our warrant for the abolition of slavery in every State of the Union.”

This reminds me of Robert Heinlein’s opposition to the military Draft due to its contradiction of the Constitution. Heinlein considered conscription “involuntary servitude, immoral, and unconstitutional no matter what the Supreme Court says.” (I agree. To be forced into the collective sin of war is nothing short of inhumane and, frankly, atrocious.) Regardless of the apparent hypocrisy and normative participation in the basically worldwide slave trade of some American Forefathers (most notably Thomas Jefferson, who wrote of slaveholders’ deserved holy reckoning), the spirit – and, to Douglass et al., the letter – of the Constitution prescribed manumission and endorsed liberty nevertheless. In 1852 Douglass condemned oppression “in the name of humanity, which is outraged, in the name of liberty, which is fettered, in the name of the Constitution and the Bible, which are disregarded and trampled upon.” And Martin Luther King, Jr.’s evocation of America’s foundational aspirations in his 1963 “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” mustn’t be omitted here:

One day the South will know that when these disinherited children of God sat down at lunch counters, they were in reality standing up for what is best in the American dream and for the most sacred values in our Judaeo Christian heritage, thereby bringing our nation back to those great wells of democracy which were dug deep by the founding fathers in their formulation of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence.

The unique might of those grand seminal documents allowed for sight among blindness. In his Life and Times Douglass described his redemptive epiphany: “Light had penetrated the moral dungeon where I had lain…Liberty, as the inestimable birthright of every man, converted every object into an asserter of this right. I heard it in every sound, and saw it in every object.” Whether acknowledged or not by the Forefathers, “the moral dungeon” was bound to be penetrated by the very light they’d ignited. Douglass took that seriously, and he chastised shirkers of that light with great seriousness.

His abolitionism was existential, deeper than social constructs and politics. He perceived “the pride, the power and the avarice of man” as the source of inhumanity in general and slavery in particular. And, in Augustinian fashion, his chief wariness was of the fallible human soul, since, as he believed, even the smartest, most respectable people could be corrupted and could oppress. In a more positive note, however, Douglass wrote in his Life and Times that “Nature never intended that men and women should be either slaves or slaveholders.” Why? Because the volatile dichotomy is a profoundly evil chemistry: Slavery dehumanizes and distorts both parties, and it is a progressive regression, a perpetual spiritual perversion that can result in only wholesale ruination. Consider this gobsmacking passage about Captain Anthony, one of the few men who were called Douglass’ “master”:

He could, when it suited him, appear to be insensible to the claims of humanity. He could not only be deaf to the appeals of the helpless against the aggressor, but he could himself commit outrages deep, dark, and nameless. Yet he was not by nature worse than other men…A man’s character always takes its hue, more or less, from the form and color of things about him. The slaveholder, as well as the slave, was the victim of the slave system. Under the whole heavens there could be no relation more unfavorable to the development of honorable character than a slaveholder’s character than that sustained by the slaveholder to the slave.

As for what Douglass’ views might’ve been on the pertinent-at-present question of race-based reparations in the U.S., perhaps his following statement provides a clue: “I esteem myself a good, persistent hater of injustice and oppression, but my resentment ceases when they cease, and I have no heart to visit upon children the sins of their fathers.” Augustinian, yes. But Douglass refused to allow original sins to damn the future.

“Mix It Up”

Mix it up until there are no pedigrees.

– “Midnight” by Red Hot Chili Peppers

Not long after his first wife, Annie, died, Douglass remarried with Helen Pitts, a white woman who was instrumental in Abolitionism and women’s voting rights, and eventually founded Washington, DC’s Frederick Douglass National Historic Site. Their relationship drew much criticism and scorn, of course, but Douglass blew off the negativity, amused that his marriage inversely mirrored his own ancestry of a white father and a black mother, a union which had produced his “mulatto” status. Being classified and self-accepted as such, Douglass embodied his central belief in the positive, salvational power of miscegenation, along with the more abstract progress of assimilated multicultural society. What better way to topple racists’ towers, to squash the concept of limpieza de sangre (blood purity) to defy Marcus Garvey’s and Cecil Rhodes’ hopes of black for black and white for white? In William Faulkner’s miraculous masterpiece (and commonly misconstrued all-American novel) Absalom, Absalom!, Quentin Compson’s dialogic partner Shreve predicts race-mixture on a grand scale: “[A]nd so in a few thousand years, I who regard you will also have sprung from the loins of African kings.” Likewise, American-treasure Jean Toomer believed that miscegenation was natural and inevitable, and that, in time, “the race” would evolve into and become part of “a common soul,” an American soul, an “American race.”

Such blending was met with horror and opposition, of course – by both blacks and whites. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. criticized the above sentiment of Toomer as “racial castration,” and odious Marcus Garvey predicted that “miscegenation will lead to the moral destruction of the races.” In 1864 a particularly influential and history-pervasive piece of anti-abolitionist propaganda came out: The Theory of Blending the Races, Applied to the American White Man and Negro. Up there in hysterical hoaxing infamy of the anti-Jew Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion (1903), this remarkably in-depth reaction against the Emancipation Proclamation featured the coining of the term “miscegenation,” warning the so-called higher race of the impending drastic consequences of race-mixing among so-called lower peoples.

What may be most striking in the pamphlet is the fact that Irish people rank lower than black folks. According to the authors, the Irish were not only “a striking instance of the decay of the races” throughout history, but they also were “brutal, ignorant, and barbarous, lacking in everything which goes to make up a prosperous and enlightened community.” Plus, driven by their lustful preference for black men, Irish women were prone to procreating with them and thus elevating the apparently profane Irish race, which was considered “more brutal” and “lower in civilization than the negro.” As far as collectivist stupidity goes, this is an amusing ironic inversion of the more common alarm over dilution of so-called white blood by duskier kinds. (Then again, the Irish weren’t even considered white by the phobic fools of that time.)

Now, needless to say, I think both dating and mating interracially and within one’s race are cool. Human relationships should depend on attraction, compatibility, love, desire – whatever. In his Eugenics and Other Evils, G.K. Chesterton defended “letting people marry anyone they like,” contending that “sexual selection, or what Christians call falling in love, is a part of man which in the rough and in the long run can be trusted” and a force that destroys the poison science of eugenics. Miscegenation might not be the solution to racism, but it certainly isn’t a detriment. What poisons is collectivist dehumanization of individuals, so race-alone motivations and strictures should be avoided. And sometimes bold choices, against social grains and according to one’s authentic, confident flow, are needed to disrupt oppressive paradigms. Frederick Douglass’ precocious marital decision was such a bold choice. Also, his acknowledgement of his biracialness, as opposed to adhering to and perpetuating the problematic “one-drop rule” in regard to so-called black blood and white blood, undermined the weird eugenics of the time – which flourishes to this day, thanks to the sugar-coating of racial pride.

I used a passage from Sutton Grigg’s 1905 novel, The Hindered Hand, as an epigraph for this digressive mess of a review, and I return to it because of Grigg’s disappointment in and sincere wariness of how the Douglass/Pitts marriage brought negative consequences to the man whom he so respected and praised. Consider this passage from the book’s Supplementary:

The marriage of Frederick Douglass to a white woman created a great gulf between himself and his people, and it is said that so great was the alienation that Mr. Douglass was never afterwards the orator that he had been. The delicate network of wires over which the inner soul conveys itself to the hearts of its hearers was totally disarranged by that marriage.

76 years after Douglass and Pitts were wed, another interracial marriage inspired similar high-profile controversy: the pairing of the great Sammy Davis, Jr. and blonde bombshell May Britt, a pairing that incensed both whites and blacks. Sammy had already defied the race barrier by dating Kim Novak – until the machinations of crooked Columbia Pictures mogul Harry Cohn and a Mob thug presented Sammy with a choice between life and death to end the relationship. Ultimately undeterred by the entrenched norm of romantic segregation, Sammy married Britt in 1960, causing intense and widespread offense, even death threats. A passage in his Yes I Can memoir captures the weirdness of his isolative racial in-betweenness:

I had a mental picture of the whole world split in half, with me standing in the middle, the Negroes on one side glaring at me and the white on the other side laughing. What do I have to accomplish before I can walk on both sides of the world in peace? With dignity?

Elsewhere in the memoir Sammy recalls the point in his life when racism first became evident to him. “Overnight the world looked different,” he wrote. “It wasn’t one color anymore.” He described racial prejudice as a thing that “had been forced on [him],” a sort of abrupt invasion. Even cultural celebrity couldn’t solve the fundamental societal conflict: “In Vegas, for twenty minutes, twice a month, our skin had no color. Then, the second we stepped off the stage, we were colored again.” “When white and black meet today, sometimes there is a ready understanding that there has been an encounter between two human beings,” Gwendolyn Brooks told Paul Angle in 1967. “But often there is only, or chiefly, an awareness that Two Colors are in the room.” Though I despise the term “woke,” this common realization is indeed a sort of awakening, but more like the Edenic loss of innocence, an eye-opening to a burdensome shame (undeserved in this case), expanded – but painful – perception. The aftermath can turn into vigilance against such shame, or a vehement counter-chauvinism, and/or a rejection of American assimilation, even a self-destructive Bigger Thomas-caliber nihilism.

But it also can, with help from the apparently peculiar “double consciousness” of which W.E.B. DuBois wrote, bolster and inspire one’s identity that much more: allowing for transcendence and genuine individuality beyond limiting classifications. So, instead of accepting the abuse brought via “self-questioning, self-disparagement, and lowering of ideals,” one can move forward with a decent measure of volition and efficacy. (Self-questioning should never be thrown out with dirty spiritual bathwater, however. Self-questioning is a check-and-balance phenomenon among all races – or should be.)

The profound but ambivalent existential situation of blacks in America in Douglass’ time (before, during and after the Civil War), through the Jim Crow era and beyond always puts the American nation itself in question at least and on trial at most. The extent to which this is warranted and sensible would be better discussed elsewhere, but whenever the subject pops up, I refer to Chesterton’s famous line from The Defendant (1901): “‘My country, right or wrong,’ is a thing that no patriot would think of saying. It is like saying, ‘My mother, drunk or sober.’” A similar attitude was regularly expressed by James Baldwin decades later. “I love America more than any other country in this world,” he wrote in “Notes of a Native Son,” “and, exactly for this reason, I insist on the right to criticize her perpetually.”

Chesterton rejected the warts-and-all brand of patriotism, but touted patriotism fundamentally. Citizens experience and participate in patriotism in different ways. Of course, many are born into it and just carry it on, like a genetic predisposition, throughout their lives. Others step back, examine it, evaluate the degree of their inclusion and dignity in it, and act accordingly with acceptance, ambivalence or repudiation. What’s particularly interesting about the apparently common sense of ambiguity in the topsy-turvy, glorious but bloodstained, often uplifting/often problematic, certainly grand American system is the effect relativity has in clarifying its finer points and/or, at least, revealing America’s penetrative power on its citizens’ identities and worldviews. Tellingly, this can become evident as a result of departing from the country in search of outside, even alien, experience.

Consider what Gwendolyn Brooks said to Sheldon Hackney in a 1994 Humanities interview:

But traveling to other countries helps you italicize American positives. Once you get out of the country, whatever your woes, your wobblinesses, your confusion, your fury, you find that you are operationally an American. I myself am forced to realize that I am claimed by no other country. My kind is claimed by this country, albeit reluctantly. Furthermore, traveling teaches you that cruelty and supersedence [sic] are everywhere.

My mind immediately goes to jazz saxophonist Oliver Nelson in a 1972 interview with John Cobley. “…I’ve been to Africa, and I’m saying Africa is not where it is” and “the place to start thinking about making a living is in this country, America, although Africa was very nice to visit.” Also, in another interview Nelson, always willing to opine about the myopia of “Mother Country” enthusiasts, recalled how the blacks in Africa tended to snub him and his bandmates, discounting them as “mixed bloods.”

Literally named after quintessentially American Ralph Waldo Emerson, Ralph Ellison, who was anything but a passive assimilator, insisted: “While I am without doubt a Negro, and a writer, I am also an American writer.” And Sammy Davis, Jr. asserted his Americanism despite the many ignoble aspects of the nation and its people: “Despite all the problems, America is still the best country in the world.” He didn’t revere America for its treatment of him, but because he considered America “mine.” Frederick Douglass seems that he would take that strong notion a step farther, judging by his equation of American nationality with literal incarnation, writing in “Why is the Negro Lynched?”: “[T]he native land of the American Negro is America. His bones, his muscles, his sinews, are all American.”

This isn’t to say that Douglass condoned absolute apologism for the sake of this nativity, any more than it’d be sensible to stoically accept the state of one’s body despite illness or disease. In fact, in what is perhaps his fieriest work, “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?,” a speech given at the 1852 Declaration of Independence commemoration in Rochester, New York, Douglass blasted American hypocrisy and the sin of slavery’s unjust legality: “Whether we turn to the declarations of the past, or to the professions of the present, the conduct of the nation seems equally hideous and revolting. America is false to the past, false to the present, and solemnly binds herself to be false to the future.”

By 1883, at the National Negro Convention, Douglass called himself “an uneasy Republican” and he declared that “if the Republican Party cannot stand a demand for justice and fair play, it ought to go down.” And a decade later he said in his introduction to The Reason Why the Colored American is Not in the World’s Columbian Exposition:

The Americans are a great and magnanimous people and this great exposition adds greatly to their honor and renown, but in the pride of their success they have cause for repentance as well as complaisance, and for shame as well as for glory…

Like George Orwell’s wise “power of facing unpleasant facts,” Douglass was capable of cradling the baby and disposing of the dirty bathwater, relishing the honey and spitting out the bees. So was James Baldwin, who clutched the tail of the sinful tiger no matter what, as shown in his debate with William F. Buckley, Jr. at the Cambridge Union Society in 1965:

The Southern oligarchy which has still today so very much power in Washington, and therefore some power in the world was created by my labor and my sweat and the violation of my women and the murder of my children. This, in the land of the free, the home of the brave. None can challenge this statement. It is a matter of historical record.

There are those who shrug off the long, pervasive norm of slavery and related or unrelated racism, focusing instead on vast social strides of integration and cultural respect. And there are many others who, though admitting improvements here and there, see present poisons of inherence, and morphed and more covert – if not blatant – kinetic legacies of Jim Crow. Both views are worthy and should be blended for a clearer, wiser perspective.

Even underrated Thomas Sowell, who is both respected and condemned for his conservatism, as well as his sociological observations, warns readers in Race and Culture that “it is a terrible mistake, with dangerous consequences, to imagine that time itself improves relations among racial and ethnic groups.” And Stanford University historian George Fredrickson points out that “one does not of course have to believe that prejudice is literally innate or instinctual to find an enduring racism in white American culture,” since “more than two hundred years of slavery and discrimination had planted the notion of black ‘otherness’ and inferiority so deeply into the white psyche that liberation of blacks from bondage could not remove it.” There’s much in that statement that seems to jibe with another core Sowell insight: that slavery doesn’t necessarily stem from racism, but vice versa, and that the otherness intensifies and becomes more despised because of slavery’s corrupting dehumanization.

Social history rocks and rolls; prejudices and paranoia ebb and flow; spiritual monsters fluctuate between slumber and tantrum. The hell-on-Earth berserker evil of the Rwandan Genocide in the early 1990s is a perfect example of this, and the surges of pogroms throughout history are relatively regular reminders. If we’re aware of the complex situation of race relations, we’re less shocked when “old” attitudes and atrocities arise, just as we can be appreciative of pervasive transcendence without utopian naivete or blindness.

Douglass’ Republicanism is a key focus in Black Prophetic Fire, a priceless textual presentation of dialogues on civil-rights Titans by living-legend (and genius) Cornel West and Christa Buschendorf. Christina points out that quite often “Douglass the ‘race man’ is juxtaposed with the ‘Republican party man,’” wondering if his pragmatism diluted his empathy for blacks’ plight in his day. West breaks down Douglass’ activism into three phases: the initial disruptive, manumitting phase, followed by a phase of continued embattlement for equal rights, and a third phase of distracted nationalism and patriotism. “[H]e is relatively silent against Jim Crow,” West says, “and his refusal to speak out boldly, openly, publicly, courageously against barbarism in the South is troubling.” Of course, this is attributed to the powerful lulling of the elitist establishment, and West goes as far as to condemn the “self-made” attitude that Douglass presented. (I’m sure Douglass’ esteem for the sanctity of private property and capitalism in general irks West as well.)

“This paradox between self-reform and outside philanthropy at times confounded his conception of Reconstruction, thereby undermining its viability,” wrote Waldo E. Martin, Jr. in The Mind of Frederick Douglass. Martin goes on to emphasize Douglass’ emphasis on merit over racial preferences, a view that probably would have soured Douglass against the future concept of Affirmative Action. He also touches on another crucial aspect of Douglass’ perception of race that I happen to champion and share all the time: the cut-from-similar-cloth nature of both racial pride and racial shame/shaming. For me, and, I assume, for Douglass, racial pride is essentially collectivist poppycock, just as is race shame/shaming. Generally speaking, kind-pride plants the seeds and quickens the germination of chauvinism, and chauvinism blossoms with oppressiveness.

The Parakeet and the Window

So, in these days of common biographical/fantastic fan fiction of historical figures, how might the illustrious life of the great – and quintessentially American – Frederick Douglass be adapted? For me, true stories made into comic books are rarely attractive. It’s difficult to explain exactly why, but let’s just say that I prefer some fantasy, some surreality, some freeing fiction to straightforward historical portrayals – which isn’t to say that I’m thrilled by fictionalized historic figures. If you’re going to present a hero who’s a former president or a Jane Austen character…just effing create your own character. Goofing around with and cameoing actual people who once lived in the style and with the finesse of, say, Alan Moore and Neil Gaiman is right on, however.

But I think comic-book adaptations of biographies and autobiographies seldom work. There’s either not enough information or too much (lots of bulky chunks of narrative text), and, more often than not, the art sucks. Maybe I see such projects as writers and artists trying to push genies into bottles, or proliferation of what seems to be glorified CliffsNotes. Sure, I see the positive intention in publishers that pump out illustrated non-fiction, such as capstone’s Graphic Library, which offers everything from Babe Ruth to the Vikings to Billie Jean King, but I’d rather my own children get their crucial historical foundation from text-only sources. Then eff around with comic-book versions.

“Put simply, the comic book medium’s unique and highly stylized combination of printed words and sequentially ordered drawings expands the concept of ‘reading’ beyond the conventional, literary sense of the term,” writes Jeffrey Brown in Black Superheroes, Milestone Comics, and Their Fans, which chronicles and analyzes the precious phenomenon of DC’s black-run imprint, Milestone, back in the 1990s.

The trick comic books have to perform is to combine the powerful word with the more powerful image, with effective balance, to do justice to whatever material is being presented. Big ideas, serious concepts and metaphysical import can be conveyed by fantastic comics – particularly superhero ones – more than non-fiction ones. “Comics abstract and simplify,” goes a line in the introduction of The Blacker the Ink: Constructions of Black Identity in Comics & Sequential Art. With at least a tinge of disapproval, the author adds that “comics, in some sense already abstract, can also become even more abstract.” But, rather than metaphysical/conceptual anemia, I think such abstraction can produce the profundity of myth. “The more lucidly we think, the more we are cut off: the more deeply we enter reality, the less we can think,” said C.S. Lewis, referring to myth’s power. In myth “you [are] not knowing, but tasting; but what you were tasting turns out to be a universal principle.”

As much as Milestone stands out as splendidly peculiar in the mainstream comics industry, and as much as I half-appreciate the “nobody looked like or were relatable for us in comics until recently” sob story of too many (commonly obtuse) critics, for quite a while there’ve been very worthy black superheroes, ones transcending the goofy “Sweet Christmas!” “street” slang of Power Man back in the dawn of the 1970s. Earlier heroes, such as Black Panther, Storm, Falcon and Blade, aside, before Milestone’s debut, there are Gerard Jones’ and Cully Hamner’s brief-but-brilliant Green Lantern: Mosaic series. And, of course, Todd McFarlane’s Spawn, featuring a black protagonist, also predates Milestone, though McFarlane claims that his intention was to “rip off the skin” in order to reduce skin color to “a non-issue” and, hopefully, expunge it from collective memory. Nice sentiment, but skin color will never be forgotten, let alone overlooked – nor should it be. It’s color; it’s a trait; it’s visible; it’s part of the grand versatility of the miracle of human bodies.

Among my favorite titles of Milestone Comics’ repertoire of masterpieces (Blood Syndicate, Shadow Cabinet and Xombi) is Hardware, done by genius Dwayne McDuffie and Denys Cowan. Living in a situation slightly similar to Tony Stark/Iron Man, scientist Curtis Metcalf is a singular Fifth Columnist, so to speak, in the corporation of his white nemesis, tycoon inventor Edwin Alva. The first page of the series’ first issue features Metcalf’s narration about his childhood pet parakeet that would repeatedly escape from its cage and smack into the glass of a nearby closed window, “a barrier of glass, unseen and incomprehensible to him.” The lesson learned by this futile recurrence was that the parakeet “mistook being out of his cage…for being free” and that “escape is impossible until one perceives all of the barriers.”

Disillusioned and aware that Edwin Alva is an exploiter and a criminal, Metcalf realizes that “Alva became wealthy on the fruits of [his] genius.” Metcalf was brought up and conditioned to be a slave of a sort. And, alluding to institutional slavery’s perverse version of paternalism, he reaches an intense conclusion: “All the evils I battle have one father. And in more ways than one. He’s also my father.” In contrast, my mind instantly goes to one of a couple of the most striking lines in Frederick Douglass’ autobiography: “Of my father I know nothing. Slavery had no recognition of fathers, as none of families.”

Metcalf envisions his inevitable revenge on Alva and acknowledges that “a purifying, white-hot stream” of vengeance is quite near, but “it feels so wrong.” Instead of freeing himself from his figurative cage, his desire for revenge has complicated his imprisonment. This ironic lesson recapitulates essentially in an arc that involves Hardware’s clash with a vigilante-turned-villain named Deathwish, whose trauma at watching the rape and murder of his wife and son inspires a reckless rampage of unilateral executions. Horribly, when the single-minded crusader blacks out he slaughters prostitutes in serial fashion. Deathwish ends up no better than the atrocity from his past. During a haunting vision of self-judgement, Metcalf sees an imaginary Edwin Alva, who says that “the right ends can justify any means” and that one’s duty necessitates such a brutal path. Thankfully, Metcalf/Hardware learns that justice is worthier than vengeance.

Then again, some parakeets burst from their cages, demolish their windows and take the path of brutality beyond. This is what happened in the case of Nat Turner, the slave who in 1831 led a rebellion that resulted in 55 dead whites, including a beheaded baby. The grisly story was chronicled in 1837’sThe Confessions of Nat Turner and later novelized by William Styron in 1967. And, more germane to this spiel, it also was adapted as a graphic novel by comic-book writer/artist Kyle Baker, whom I came to respect, along with penciler Andrew Helfer, via the late-1980s The Shadow series. Nat Turner is full of explicit violence, but there’s not a definite castigation of Turner’s choice of recompense for his and his people’s suffering. Understandably, such omission of righteousness tends to bother many folks, not to mention how much more bothersome implicit assent by authors is.

In his 1966 review of Truman Capote’s true-crime novel In Cold Blood Eliot Fremont-Smith recognizes in the book’s presentation of “a crucial revelation of the dichotomy between the moral judgment of an act and the moral judgment of the person who commits,” which, to him, “seems the only coherent way to confront one’s horror, one’s condemnation of the crime and sorrow for the victims and one’s sympathy for the perpetrators of the crime.” “Finally, Nat [Turner] has an inspiration,” Kyle Baker said in a Pop Image interview. “Nat organizes an armed slave revolt and a lot of people get killed in big action scenes.”

Compare that to the earlier stuff about McDuffie’s comic-book hero and our man of the hour, Frederick Douglass, who, like Metcalf/Hardware, when faced with the option of going down the violent path of his radically abolitionist friend John Brown. Invited to the insurrection by Brown, Douglass chose not to be part of the rage that culminated in the massacre at Harpers Ferry. In his future speech, “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” (1852), Douglass perhaps summed up the differences in his and Brown’s reformatory styles. He spoke of streams either providing Earth with refreshment and fertilization – or rising up “in wrath and fury, and bear[ing] away, on their angry waves, the accumulated wealth of years of toil and hardship.”

Rather than nobility or mercy, Douglass admits: “My discretion or my cowardice made me proof against the dear old man’s eloquence – perhaps it was something of both which determined my course. Here we separated; they to go to Harper’s Ferry, I to Rochester.” I wonder if Douglass’ prior epiphany of the mutual distortion of oppressed and oppressor, who are “both victims to the same overshadowing evil,” tempered his spirit and enabled him to take a different course. He believed that he’d “penetrated to the secret of all slavery and of all oppression” and isolated the central culprit: “the pride, the power and the avarice of man.” From then on Douglass saw human existence with keener vision:

Light had penetrated the moral dungeon where I had lain, and I saw the bloody whip for my back and the iron chain for my feet, and my good, kind master was the author of my situation…Liberty, as the inestimable birthright of every man, converted every object into an asserter of this right. I heard it in every sound, and saw it in every object.

“Words are Weapons, Sharper Than Knives…”

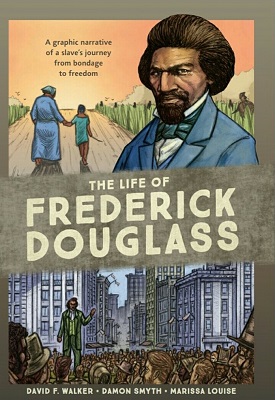

As a lyric from “Devil Inside” by INXS goes, “words are weapons, sharper than knives,” and Frederick Douglass certainly wielded words sharply – wisely, swiftly and incisively. But the importance of praxis over logocentrism is expressed by crusader John Brown in a new graphic-novelization of Douglass’ life, The Life of Frederick Douglass: A Graphic Narrative of a Slave’s Journey from Bondage to Freedom: “Words cannot end slavery, Frederick.” Thanks to author David F. Walker, illustrator Damon Smythe and colorist Marissa Louise, history explorers and comic-book fans alike can follow the real exploits of a man whose words, inspired much by the very unique words of the Declaration of Independence and Constitution, did help to undermine and ban slavery in America.

In his introduction, David Walker notes that the writing of the graphic novel relies mostly on Douglass’ own autobiography, though much of the text is paraphrased (or distilled, as Walker puts it). Also, for Walker, Douglass is revered as “something of a mythological figure,” on par with the likes of United States’ first president, George Washington, and the president of Emancipation, Abraham Lincoln. Common to many comic book-style true stories, a Who’s Who is provided at the beginning. The cast includes grandmother Betsey Bailey, mother Harriet Bailey, first wife Anna Douglass, the Douglass children, Douglass’ first “owner” (and suspected biological father) Aaron Anthony, and rotten “slave breaker” Edward Covey. Then the book starts with Douglass sitting down to write down his life, which has since risen to mythic status. “I have been kept in chains, and I have conferred with Presidents,” goes the narration. “I have been beaten, and I have fought back.”

Confused and not yet blessed with the weathervane wisdom that launched him from lowness to glory, young Douglass is escorted to the “Great House” of slaveowner Aaron Anthony’s plantation by his grandmother, who leaves him there in pain and incomprehension: a slave.

David Walker provides an expository section called “A Brief History of Slavery in America,” which covers the time from 1619 to 1863, the year of Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, and highlights the largely unsung fact of John Punch, the first life-sentenced slave in colonial times. With that knowledge, readers can move on, guided by narrator Douglass, to the following section, “Coming to Understand Slavery.” There the incomprehensibility of slavery is summed up: “It is difficult…to find the words to convey the reality of being a slave.” But words of conveyance became Douglass’ specialty relatively early on. Thanks to his observational power and intelligence, he starting forming that linguistic virtuosity for which he is so famous. “Choose your words well,” Douglass overheard a tutor named Joel Page say to slaveowner-son Daniel. “Speak with authority and clarity. Allow the manner of your articulation to define you as a young man of culture and intelligence.”

By the time Douglass was sent to Hugh and Sophia Auld in Baltimore he was reading aloud from the Bible, for Hugh’s pleasure. Thanks to the power of imagery, readers see Douglass’ guarded face become a scowl as he reads an ominous passage from Psalm 27: “The Lord is the strength of my life…of whom shall I be afraid? When the wicked, even mine enemies and my foes, came upon me to eat up my flesh, they stumbled and fell.” It’s in episodes such as this one that the graphic-novel medium particularly glows.

Officially not a full human being, at least according to the odious system in which he was enslaved, eventually Douglass eventually asserted his full humanity figuratively and literally when he resisted the devil Edward Covey: “I was nothing before, but now I was a man.” His fateful escape came under the rule of a William Freeland, during which Douglass established a Sunday school for some of the fellow hands, including a Sandy Jenkins and brothers Henry and John Harris. “My task was not only to bring the word of God to their hearts,” Douglass says, “but also to bring the ability to read and write to their minds.” Early on, there was the man whose logocentrism would eventually lead to redemptive deeds.

Following an arrest and an apprenticeship to a shipbuilder named William Gardiner (via Hugh Auld), Douglass met the woman who would become his first wife, Anna, and escaped to New York City, where he became affiliated with the Underground Railroad before relocating to Bedford. There he was aided by a Nathan and Mary Johnson. Nathan suggested a new surname for Frederick: based on the Douglas character from Sir Walter Scott’s “Lady of the Lake” poem. (An extra s was added, of course.)

Destiny coalesced for Douglass when he met The Liberator’s William Lloyd Garrison, whose abolitionism still makes history tremble. Using his talent for oratory, Douglass began public speaking, which often featured his emphatic claim of being claimed by the country of both his enslavement and liberation. David Walker boils this down in the Graphic Narrative:

…I am an American! I know little of Africa, for it is not my home…America is my home. I am a product of its greatest sin, and I will not leave my home simply to appease the guilty conscience of a nation.

Frederick Douglass was born an American, became and lived as a quintessential American, and died an American.

Die as Born

In this relatively thorough book, Walker focuses on the buzz of condescending whites as Douglass’s popularity rises. “He is so articulate and well-spoken,” says one grimacing guy in an audience, for instance. Assuming that this is included as a comment on the offensive trope of spotlighting proper, effectively communicating minorities as if they are surprising anomalies, I’m reminded of foot-in-mouth Joe Biden’s praise of pre-presidential Barack Obama as “the first mainstream African-American who is articulate and bright and clean and a nice-looking guy.” (My Lord!) “My skin color was used to deny my humanity,” goes Walker’s Douglass’ narration, “while my intellect and the articulation of my experiences were used to call into question the validity of my narrative.”

Mr. Biden, if you’re reading this, please note that President Obama was far from being the first articulate, bright, clean (biracial!) person with African heritage. Though there are countless such folks in between, please meet Frederick Douglass, Mr. Biden. As Walker points out, Douglass was so august and recognized, that he, besides being a major mover and shaker of American history, may have shown up in photographs more than anyone else in nineteenth-century America – even more than Abe Lincoln. This is revealed in my favorite section of the book: “Photography and Frederick Douglass.”

Noting that Douglass’s first photographic portrait was taken only two years after Daguerre introduced the daguerreotype process to the world, Walker tells us that “Douglass would go on to write and speak about the power of pictures, firm in his belief that photography was one of the most effective weapons in fighting the negative representation of blacks depicted in other visual media…By comparison, photographs captured the truth.” This reminds me of the uplifting, dignified photography of James Van Der Zee and Carl Van Vechten, as well as the paintings of Aaron Douglas and Archibald Motley, Jr.

There’s a time and a place for idealization, and there’s a fine line between pride in accomplishment and unrest over the sorely unaccomplished. As Walker points out, the very way Douglass posed for photos, and, mainly, the rareness of his smiles, indicated his existential state: “In many pictures, his eyes are cast directly at the camera, an uncommon practice at the time, which resulted in a seemingly defiant expression…[H]e never wanted to be portrayed as content or happy with his condition and the condition of other blacks in America.” Even after negating his fugitive status by paying off Hugh Auld, Douglass surely remained sensitive to the infernal pain of human bondage. Prescient as ever, this compulsion toward universal freedom inspired his association of women’s rights to the rights of blacks.

Perhaps one of the things that interests me most about Douglass’s life is the bitter rift between him and William Lloyd Garrison over the trajectory of abolitionism and, in particular, the nature of the Constitution, so I’m pleased that the Graphic Narrative covers this nicely. It also covers the other significant divergence: his parting from the proponent of atrocious activism, John Brown. Staying true to the actual Life and Times, Walker mentions Douglass’ admission of possible cowardice, rather than morality, being the deterrent, though Walker seems to have consolidated Brown’s failed Kansas insurrection and the later Harper’s Ferry incident.

Approving of Brown’s ends but not his means, Walker’s Douglass says: “Committed as I was to the abolition of slavery, I could not bring myself to sacrifice my life.” Here’s how Douglass puts the situation in the actual Life and Times:

My answer to this has already been given; at least impliedly given – “The tools to those who can use them!” Let every man work for the abolition of slavery in his own way. I would help all and hinder none. My position in regard to the Harper’s Ferry insurrection may be easily inferred from these remarks, and I shall be glad if those papers which have spoken of me in connection with it would find room for this brief statement.

Speaking of means and ends, Walker wisely includes a section called “A Brief History of the Civil War,” in which he covers the impetus for the North/South conflict and the real role President Lincoln played in all of it. Restoration of the Union was the practical main goal for him, for sure, which is no wonder, since national coherence is a huge presidential duty. It took some time, a lot of mishaps and much counsel from Douglass for the overburdened president to put abolition at the forefront. Douglass puts it this way in Life and Times:

And many and grievous disasters on flood and field were needed to educate the loyal nation and President Lincoln up to the realization of the necessity, not to say justice, of this position, and many devices, intermediate steps, and make-shifts were suggested to smooth the way to the ultimate policy of freeing the slave, and arming the freedmen.

Lincoln had his wishy-washiness in regard to the black race earlier on and even into his heyday. But, as the Graphic Narrative points out, Douglass “did not shy away from criticism of” the noble leader of the Union. I always liken the Lincoln/Douglass relationship to that of MLK and JFK, which is chronicled in Steven Levingston’s wonderful Kennedy and King book. “Douglass…you are a man of great conviction,” Walker has Lincoln say. “You have not held back your criticism, and it is with that in mind I need your wisdom.” Asked for advice on both Lincoln’s reelection and the war, Douglass produces a written plan based on John Brown’s earlier strategy and on Harriet Tubman’s methodology.

Sadly, the Dream Team of Abe and Fred comes to an end with America’s first assassination of a president. “I mourned him as a man prone to moments of both greatness and fallible shortcomings,” says Douglass in the Graphic Narrative. “I mourned him as someone whose mind was not fixed by solitary notions, but open to an expansion of ideas and philosophies.” In Life and Times he goes farther with his praise: “Mr. Lincoln was not only a great President, but a great man – too great to be small in anything.” And, more significantly, Douglass emphasizes that Lincoln was never elitist or condescending during their talks. His fundamental kindness and sincere respect were noticed.

Having helped with the Underground Railroad as a “stationmaster” and revered Emancipation Proclamation, an on-fire Douglass insisted on the need for black soldiers in the war, which required audience with Lincoln himself. In the Graphic Narrative Douglass is shown spelling out the cruciality of slavery’s total elimination via a two-page monologue, orating unequivocal statements such as “We cannot restore the Union or honor the Constitution if we continue to bow before the strongman that has brought both to its knees” and “No war but abolition war! No peace but an abolition peace! Liberty for all, and chains for none!”

What Frederick Douglass battled against was dehumanization itself, and what is both symbol and reality of dehumanization was enslavement. A champion of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, he believed that humans are born free and that they should live – and leave life – free. David Walker’s underlying purpose for completing this project is revealed on the book’s final page: “Dedicated the memory of those who came before me, and endured the dehumanization of slavery…[T]hey were more than property, they were human beings, and they are the past from which I came.” This fundamental celebration of the maintenance of every individual’s humanity is a line Walker wrote in regard to Douglass’ death from a massive heart attack in 1895: “He died as he was born – a human being.”

In the book’s final section, “Later Years,” the narrative covers Douglass’ public speaking, activism (in women’s suffrage, notably), editorship, careers and political professions that followed the war and Lincoln’s passing. His achievement, efficacy, gravitas and merit are all impressive, for sure, but all the glorious noise of politics and ontological rocks and rolls is hushed when, thanks to the minds behind the Graphic Narrative, a very changed Douglass visits former slaveowner Thomas Auld, who is dying, in 1877. More than 40 years has passed since their horrible connection, and now they meet on a saner level. “Marshal Douglass,” says Auld in deferential greeting, referring to Douglass’ official status in Washington, DC. The nobly humble reply: “Frederick Douglass. I am not here as a Marshal, merely as a man, Captain Auld.”

“I wish I could undo all that has been done,” regretful Auld admits, but Douglass is magnanimous and wisely stoical: “All that has been done is what made me who I am.” Much more about this profound, affecting meeting is relayed in Life and Times. In actuality, Auld offered an apparently sincere (though too-little-too-late) condemnation of the slave system, followed by the revelation of his care for and support of Douglass’ grandmother for “as long as she lived,” though he never owned her. “[A]ll the circumstances of his condition affected me deeply,” Douglass writes of Auld, “and for a time choked my voice and made me speechless.”

Imagine that: Frederick Douglass, a master of words and oratory, unable to speak. Such moments of regret, revelation and spiritual restitution tend to void voice and verbosity and force the heart to absorb a moment of silent emotional impact. And it’s that wordless power that rests in restless, struggling, apologetic, forgiving and aspiring hearts that made Douglass’ words so powerful. I’m pleased that David Walker, Damon Smythe and Marissa Louise shared the words, the heart, the power and the humanity of Frederick Douglass, one of America’s peerless treasures.

by David Herrle