Rating: ❤❤❤❤❤

He used to say, over and over, every day he would put on his cemetery clothes.

– Cornel West, Black Prophetic Power

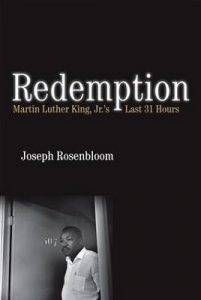

When MLK was assassinated in 1968, young journalist Joseph Rosenbloom decided to eventually investigate and tell “what happened in Memphis leading to the violent finale to King’s life.” Fifty years later an older Rosenbloom has fulfilled this idea in Redemption: Martin Luther King Jr.’s Last 31 Hours, an instant paragon of MLK scholarship. Most recently enthralled by Steven Levingston’s Kennedy and King and appreciative of Tavis Smiley’s Death of a King, I welcomed this refreshingly svelte volume about the coda of the man’s profoundest period.

Let’s begin at the end. At 5:55 p.m. on April 4, 1968, while in Room 306 at the black-owned – and assassin-friendly – Lorraine Motel, the room he shared with Ralph Abernathy, Martin Luther King Jr. got a dinner reminder from friend Billy Kyles and replied, “I’ll wait on the balcony.” Six minutes later he was shot to death. As Rosenbloom writes, “a bullet struck him on the right side of the face, traveled through his neck, and came to rest on the left side of his back, splintering his spinal column.” (This is a PG-rated version of the grisly damage.) The thing that King feared and anticipated most happened. Tenser than ever, Memphis seemed hungry for his blood, and his murder is forever interpretable as a sort of atonement. Rosenbloom notes that “he was drawing deeply on his faith in the redemptive power of sacrifice for a noble cause, as he risked his life – a faith rooted in the biblical example of Jesus.” However, Rosenbloom clarifies that King sought longevity (something he stressed explicitly in his final speech), not martyrdom. Of course, even aspiring martyrs’ knees would buckle under the pressure and danger King endured from day to day.

Despite his worry and his colleagues’ concern for his safety, King came to the conclusion that nothing could really stop a driven person from executing him. After all, if JFK – a president – could be targeted successfully, why not him? With magnificent self-control and bravery, King accepted his suffering as necessary:

He tried to buffer his fear by developing a numb fatalism, a defense against the dread that someone might kill him at any moment. If dying was inevitable, he reckoned, he might as well resign himself to it. He girded himself mentally against the nerve-racking despair of constant panic. “He was philosophical about his death,” Andrew Young would recall. He knew it would come, and he just decided, you know, there was nothing to do about it.”

Sure enough, as the accepted narrative goes, a troubled loser named James Earl Ray arrived in Memphis on April 3rd. A pathetic product of bad upbringing, poverty, crime, tragedy, failure and incarceration, he had escaped from Jeff City prison the year before. His apparent hatred of blacks compelled him to purchase a Remington 30-aught-6 rifle with which to hunt down and slay the man whom Senator Robert Byrd called a “self-seeking rabble rouser” and LBJ (a favorite of many a liberal to this day) called a “goddamned nigger preacher.” Rosenbloom writes of Ray’s swift preparation with, I suspect, subtle cynicism toward the fortuitousness of it all, causing me to wonder if he doubts that Ray acted alone – or at all. The rooming house in which Ray settled had a shared bathroom with a convenient view of the balcony outside Room 306, and just when his quarry unwittingly presented himself for a relatively easy shot, that bathroom happened to be unoccupied, leaving Ray with the privacy and time needed to complete his malign mission.

Some of Rosenbloom’s phrases and lines hint at the detected cynicism: “luck was on his side,” “His good luck was holding,” “It was another lucky break” and “Fortunate to have the bathroom available at the moment…” That added to the suspicious behavior of the local police and the FBI is enough to justify doubt in regard to the accepted narrative of the assassination. (By the way, James Earl Ray claimed that he was a conspiratorial patsy. Sound familiar?)

The situation in Memphis was volatile in the weeks before King’s demise, to put it lightly. While in the midst of the Poor People’s Campaign, King became concerned with the fate of striking garbage-industry employees there, and he was determined to support them. The strike’s early moments were marred by vandalism and looting, which, of course, further soured public perception of the cause. Though King espoused nonviolent activism, he certainly understood where the aggression originated. In his penultimate book, Where Do We Go From Here?, King shared his disappointed but realistic view on the national situation:

[I]t cannot be taken for granted that Negroes will adhere to nonviolence under any and all conditions. Where there is a rocklike intransigence or sophisticated manipulation that mocks the empty-handed petitioner, rage replaces reason. Nonviolence is a powerful demand for reason and justice.

King wasn’t exactly America’s darling by the time he inserted himself in the Memphis mess. His criticism of the Vietnam War and wealth disparities, along with his and the SCLC’s intention to help inspire a “massive mobilization” in Washington, D.C., already had haters at full froth. And warnings and threats haunted the road to Memphis, but they weren’t taken seriously by those who were supposed to provide security.

Rosenbloom fills readers in on the strike situation, introducing union leaders Joe Warren and Taylor Rogers, and revealing the exploitation of black workers by white supervisors. He also focuses on a horrible incident that only stoked the fires of outrage. Two black workers, seeking shelter from rain in the back of a garbage truck – while white workers got to break in the cab – were crushed to death due to what was determined as an electrical accident. (Hm.)

Then there was Memphis Mayor Loeb’s backlash against the strike. Soon after King and crew returned on April 3rd Loeb pushed for a federal injunction to prevent a King-led march. Local reverend Frank McCrae described his friend Loeb as “confrontational,” but as Rosenbloom fairly notes, the Mayor “behaved respectfully, graciously toward blacks and whites,” far from being a Bull Connor-level bigot. In fact, perhaps paternalistically, Loeb believed that his opposition to the strike actually protected the outraged workers.

So, the city was far from welcoming territory for Martin Luther King Jr. “You ought to get your ass out of Memphis,” his wife, Coretta, implored. (See my review of Coretta’s My Love, My Life, My Legacy here.) One of King’s advisers, the now-legendary Andrew Young, also was cautious (probably too cautious from King’s view). He didn’t believe that King could keep it short and simple. Instead, things would surely spin out of control. Also, many SCLC staff objected to strike involvement. Epigraphed for a chapter intro is a statement by King that expresses the reason for his adamancy amidst so much hesitation: “The Movement lives or dies in Memphis.”

Also staying at the Lorraine Motel on April 3rd were twelve members of The Invaders, a Memphis-based Black Power group led by Charles Cabbage and John Burl Smith. King sought to incorporate them in the march, in spite of their disagreement over nonviolence, because he hoped that their participation would help prevent trouble. This was a desire he addressed in Where Do We Go From Here? by highlighting what he believed to be the ultimate choice for society: “nonviolent coexistence or violent coannihilation.” Perhaps he wanted to retry unlikely cooperation that he’d failed to achieve a few years before, when he attempted to recruit members of Chicago gangs for peaceful demonstration. Rosenbloom writes:

So King met with the gangs – the Vice Lords, Cobras, and Blackstone Rangers – seeking their support. It did not go well. He was stunned by their belligerence, their angry tirades, and coarse language…From the experience of Chicago he drew a lesson. As he wrote in his 1967 book, The Trumpet of Conscience, “I am convinced that even very violent temperaments can be channeled through nonviolent discipline.”

In Black Prophetic Power Cornel West points out that MLK couldn’t relate to black youth as well as Malcolm X did, and this seems to have been at play in the case of the stubborn Invaders. Compromise with them turned out to be a futile idea, and the fact that King’s assassination occurred only hours after their not-so-harmonious dismissal from the Lorraine has kept suspicion of retributive conspiracy alive for decades.

Redemption reveals much about the strikers and the conflict in Memphis. Again, tension mounted due to looters and vandals expressing themselves via what King called “the language of the unheard.” The temporary injunction against the march was granted by Judge Bailey Brown, which ignited the ire of Reverend Jim Lawson, an aspirant of Gandhian protest who was nevertheless more prone to blatant defiance than King. King struggled with a dilemma: should he rebel against the injunction or comply with federal judiciary? After all, Brown V. Board of Education and Browder V. Gayle had been decided by judges. “The federal courts have given us our greatest victories, and I cannot, in good conscience, declare war on them,” King had once said. “Government action is not the whole answer to the present crisis, but it is an important partial answer,” he wrote in Stride Toward Freedom. “Morals cannot be legislated, but behavior can be regulated.” But he also had written about disharmony between “unjust law” and “moral law” in his “Letter from Birmingham [City] Jail”: “Any law that uplifts human personality is just. Any law that degrades human personality is unjust.” Yet another quotation from Where Do We Go From Here? is apt:

Yet the average white person also has a responsibility. He has to resist the impulse to seize upon the rioter as the exclusive villain. He has to rise up with indignation against his own municipal, state and national governments to demand the necessary reforms be instituted which alone will protect them.

In the parking lot of the Lorraine King’s team was served with the injunction papers. To counter this the local NAACP recruited powerful lawyer Lucius Burch, a noble man who opposed segregation and worked to include black lawyers in Memphis Bar Association. Individualistic and strong-minded as he was, Burch’s authority was voluntarily tempered by acquaintance with the VIP of the Lorraine Motel’s Room 306:

In the presence of King, however, Burch showed a surprising humility. It was a rare instance of Burch deferring to someone, [J. Michael] Cody would say. He attributed Burch’s reaction to a kind of spell cast by King’s harmonious voice and calm manner. It was as if King possessed “an almost messianic or historical aura,” Cody would say.

This messianism is further substantiated by King’s Gethsemane-like suffering on the eve of his doom. “That night it seemed that even the Lord was turning against King,” writes Rosenbloom. “From inside his room at the Lorraine, he could hear the insistent wailing of tornado sirens.” Regularly tormented by migraines, insomnia and exhaustion, King was not well, and rather than attend a rally at the Mason Temple that night he opted to stay in his room. Abernathy went in his stead, along with Jesse Jackson, whom King forbade to speak. The crowd wanted the irreplaceable Reverend, of course, and he ended up going to the Temple and giving a 40-some-minute – now historically precious – speech.

King spoke with heavy, extraordinary language, as if competing with the portentous storm outside. Redemption’s telling is lovely and saddening at the same time:

His words reflected a soul searching as he contemplated the specter of death. He had talked many times before about his fear of dying a violent death. But it was unusual for King to dwell openly on the depth of his despair as he pondered his fear of death…This night in Memphis…he seemed near panic, anxious that he might be the target of an assassin’s bullet at any moment.

After the speech King collapsed into his chair. Abernathy said that “it was though somebody had taken a beach ball and pulled the plug out, as if all his energy had been sucked out.” I found this analogy to be clunky at first (the image of a colorful beach ball is jarring), but once it sunk in it became quite poignant, for the conclusion of the Mason Temple speech was King’s last gasp before the silence of death, despite the fact that the killing was yet to come the next day. To clarify, rather than all doom and gloom, the speech was at peak confidence and inspiration, and King rejoiced in finding enlightenment at the spiritual mountaintop: “Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord,” he said, quoting Julia Howe’s “The Battle Hymn of the Republic.”

On April 4th all of King’s energy was literally sucked out by the assassin’s bullet that he expected for so long. Mysteriously, police security ended that evening, as if clearing the way for the inevitable. King dropped to the balcony floor, and within two minutes, cops arrived – on foot – from a conveniently nearby coffee break. Anyone who has looked further into the weirdness surrounding the assassination, as well as the harassment of King by the FBI and betrayal by informants, knows that Memphis was more than just a proverbial powder keg in general: it was a shady, whispery execution zone for a single man, just as Dallas had been for JFK.

As if to lighten the sorrow of King’s death story, Redemption nears its close with his summarized life story: the fateful rise to ministry and fame since the early days at Morehouse College. The reiteration of biographical highlights that should be familiar to all admirers and emulators of Martin Luther King Jr. reminds readers of his seemingly anointed trajectory, his relentlessness and his radicalism against a corrupt order. I’m reminded of something Tavis Smiley wrote in the introduction of his Death of a King:

Ironically, his martyrdom has undermined his message. As a public figure who fearlessly challenged the status quo, he has been sanitized and oversimplified…He is no longer a threat, but merely an idealistic dreamer to be remembered for a handful of fanciful speeches.

He could have surrendered at any time, and it wasn’t as if popular encouragement sustained him in his last months – let alone his last 31 days. “At the time he is shot dead, 72 percent of Americans disapprove of him and 55 percent of Black Americans disapprove of him,” says Cornel West in Black Prophetic Fire. “He is isolated. He is alienated. He is down and out. He is wrestling with despair.” So, why did King march on? “He imagined that he would die with a sense of redemptive virtue,” writes Joseph Rosenbloom, who should be commended on composing this splendid biography. “That was the compensation he sought.”

– David Herrle